The Picassos of modern music

Almost 50 years ago, a group of Jamaican producers embarked on a series of experiments with reggae tracks that still reverberate through popular music today, writes Justin Quirk.

T

The story of popular music is impossible to separate from the technology it was created with – and particularly from the moments when that equipment was pushed beyond its limits and used to create something that its inventors never intended: when amplifiers were overdriven to distort the sounds of guitars at the birth of rock ‘n’ roll; when records were manually dragged backwards against needles to create the abrasive, scratching rhythm of hip hop; when feedback was first harnessed and turned from an electrical malfunction into a musical tool in its own right.

More like this:

– Is this the ultimate comfort song?

– The language being saved by hip hop

But perhaps no innovations have been as far-reaching as the set of boundary-smashing experiments that a small group of producers performed on multi-track recording machines and mixing desks in a handful of Jamaican studios throughout an astonishingly creative period almost 50 years ago. These pioneers created not just a vast trove of still-exhilarating recordings, but completely reinvented how a recording studio could be used, what a producer was able to do, and what listeners expected from music. It prefigured the world of electronic music which we now live in – of endless editing and rearranging, of technology as both tool and inspiration, of the producer as an artist in their own right, and of music’s entire past being broken down into individual elements to be selected, sampled and turned into something new. If it wasn’t for the genre known as dub, the whole culture of music as we know it would perhaps be unrecognisable.

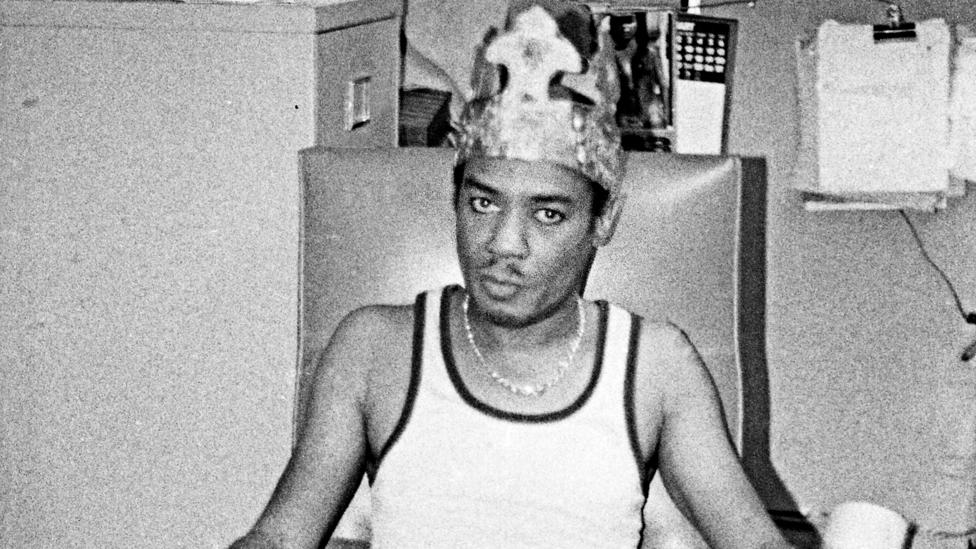

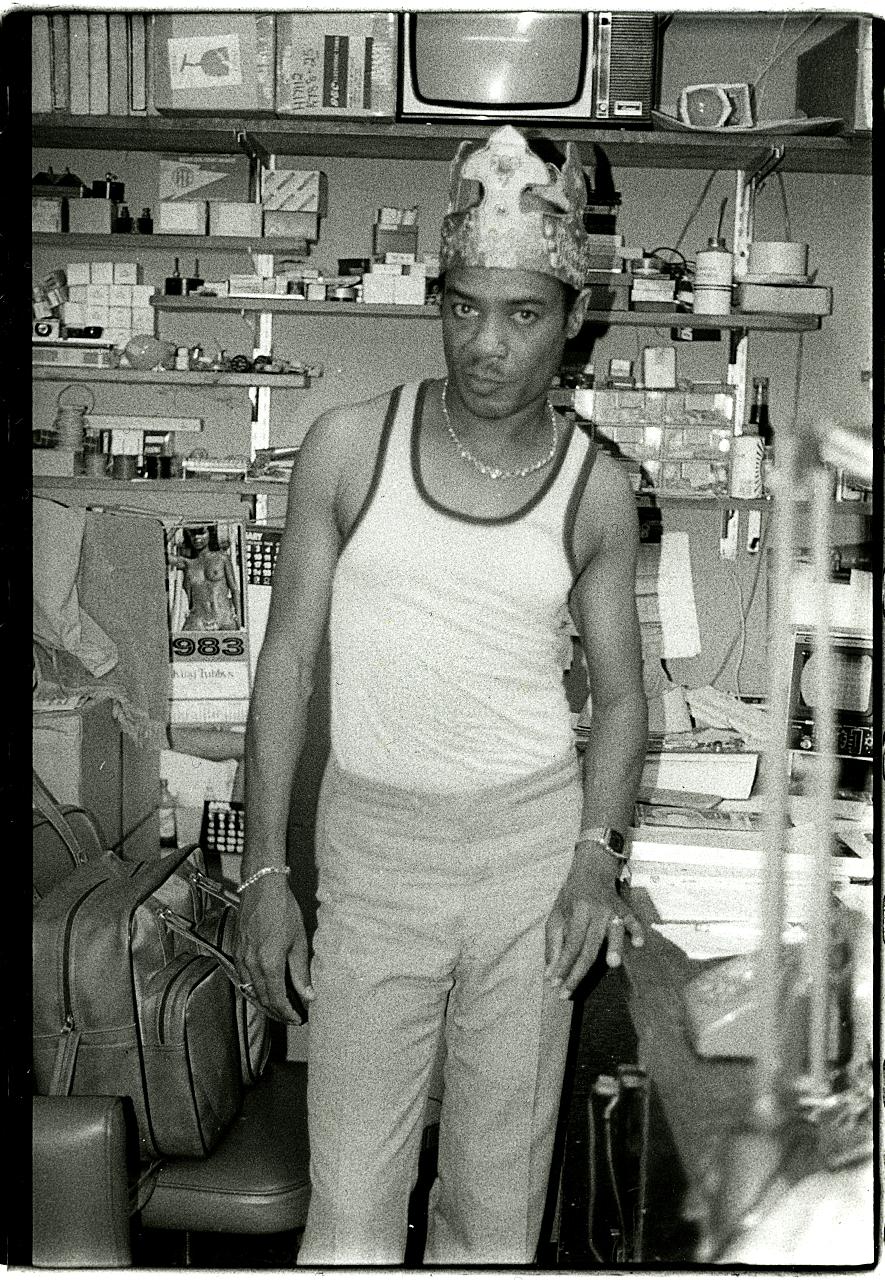

King Tubby, real name Osbourne Ruddock, was one of the pioneers of dub music, as innovative a producer as Phil Spector or George Martin (Credit: Beth Lesser)

Dub was to be the subject of a new exhibition at the Museum of London this month, which is now delayed because of the current situation, but is likely to be rescheduled for later this year. It’s a testament to the genre’s importance that such a substantial exhibition could be devoted to a style of music which produced no hit singles, had relatively limited distribution outside of its homeland, and was often created by largely faceless, pseudonymous artists. Cloaked in mystery, hard to find, and frequently baffling to casual listeners, dub may have emerged in Jamaica in the early 1970s, and had its creative heyday in the subsequent decade, but the shockwaves from that first burst of creative energy are still being felt today.

How reggae was deconstructed

Dub is, in its most basic terms, a variant branch of reggae, with producers creating radical reworkings of original – and often well-known – existing reggae tracks. But more than just remixes, dub productions are works of complete deconstruction and rebuilding, with the component parts of a recording being separated out, reordered, fed through layers of echo and reverb, and mixed into a different configuration.

The resulting tracks were often named with little connection to their parent title, further occluding their roots. So, Jacob Miller’s Baby I Love You So became Augustus Pablo’s King Tubby Meets Rockers Uptown (1974). Johnny Clarke’s King in The Arena became King Tubby’s The Champion Version (1977). Johnny Osbourne’s Give A Little Love became Scientist’s Dangerous Match Seven (1982). One song could spawn numerous dubs, all functioning as shadow selves of the original, often uncredited, track – ghostly traces of the master recording bubbling up through them, but completely different in feel and atmosphere. The dub could take on a life of its own, eclipsing the track that birthed it.

In Lloyd Bradley’s definitive history of reggae music, Bass Culture, he describes the sound of Tribesman Rockers, a 1978 reworking by Joe Gibbs and the Professionals of Lord Creator’s standard Kingston Town. “Instruments ease backwards and forwards, in, out and around the mix, completely rebalancing the tune four or five times in the space of a minute. New melodies are shaped out of bits of rhythm that have been stretched and remoulded, whereas melodic sequences have been chopped down so brutally they can be stacked on top of each other to become the rhythm.” It’s a perfect description of the complex, liquid structure of a dub.

“It always winds me up a bit when I hear people say ‘dub reggae’ – there’s no such thing. There’s reggae, then there’s a process which is applied to reggae called dub. It’s a mixing technique,” says Steve Barrow, one of the world’s leading authorities on reggae, having worked with it as a record vendor, A&R, writer and curator for more than 40 years. He was also the driving force behind Blood and Fire, the label established in 1993, and responsible for perhaps the highest quality reissue series ever of hugely significant but largely unavailable or forgotten recordings from the golden age of Jamaican music.

King Tubby’s original hi-fi dub machine, on which he first deconstructed and mixed reggae tracks into new forms (Credit: Getty Images)

Barrow describes how dub developed in Jamaica from outdoor sound systems – operations roughly akin to pop-up outdoor nightclubs that disseminated the emergent music when it had little outlet on regular radio or in Jamaica’s more established clubs. This competitive – and potentially lucrative – grass-roots circuit saw popular systems like Spanish Town’s Ruddy’s Supreme Ruler of Sound hunting for novel spins on familiar hits to give themselves an edge over their rivals. This saw them first playing instrumental b-sides, then ‘versions’ (instrumentals with a different musical topline added to them for variety) and ultimately in time – when the technology advanced sufficiently – the full deconstruction of the dub. If the ‘version’ was primarily about adding elements, the ‘dub’ was more about subtracting and reordering. “There was instrumental, then there was version, then there was dub,” says Barrow by way of chronology. “And with dub, it’s King Tubby, he’s the one who really pushed that along further than anyone else. He’s the sole progenitor of dub production in reggae.”

The king of dub

Any discussion of dub inevitably circles back to King Tubby (1941-1989), real name Osbourne Ruddock: he was as innovative a producer as Phil Spector or George Martin, and one whose achievements are even more incredible given the limited means with which he was working in his cramped home studio at 18 Dromilly Avenue in Kingston’s Waterhouse district. His major breakthrough came in 1971, when already-established ska and reggae producer and musician Byron Lee upgraded his studio, Dynamics.

Thanks to a deal brokered by fellow producer Bunny ‘Striker’ Lee, Tubby was able to acquire Dynamics’ old four-track mixer. He had previously only had a two-track machine – the number of tracks dictated how many different layers of music a producer could composite during a recording process, with more tracks equalling greater potential for depth and complexity in a finished recording. “That then gave King Tubby more possibilities – those four tracks could be separated,” explains Barrow. “If you wanted to make another version, you could bring tracks in and out of the mix.”

As a gifted electrical engineer, Tubby also had the ability to build, repair and modify audio components in a way that few others could, allowing him to push equipment beyond its usual sonic limitations, and obtain sounds and effects that were only available in his studio, most notably a distinctive, cavernous spring reverb effect. While exact dates and chronology are contested, through 1972 a number of increasingly sophisticated dub experiments appeared from Tubby and other producers like Lee Perry, with full albums following soon after as others followed their lead.

Crucially, the new dub producers like Tubby weren’t creating original songs or recording musicians as producers traditionally did, but working with tapes recorded at other studios as source material. These multi-track recordings would be fed through the mixing desk and reworked in one take into a new dub, with the end result cut straight to a unique vinyl ‘dubplate’ as it happened (this ephemeral process partly explains the often patchy nature of archiving in Jamaican music). These deeply complex, multi-layered pieces of music aren’t the result of digital editing or later overdubs – they’re essentially a document of a live performance by the producer.

A network of sonic architects grew out around King Tubby throughout the subsequent decade – Bunny Lee, Scientist, Philip Smart, Prince Jammy and more – whose names came to carry more weight on a record than those of the original performers. The idea of musical originality being of paramount importance was superseded by the idea that the mixing desk itself could be an instrument in its own right, while the track was simply source material, rather than a finished product, and the ‘authorship’ of music was a slippery, mutable thing. Perhaps fittingly, there’s no fixed agreement even on what the first true dub album was – strong contenders include Herman Chin-Loy’s Aquarius Dub, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry’s Blackboard Jungle Dub and Joe Gibbs’ Dub Serial, which all emerged around 1973.

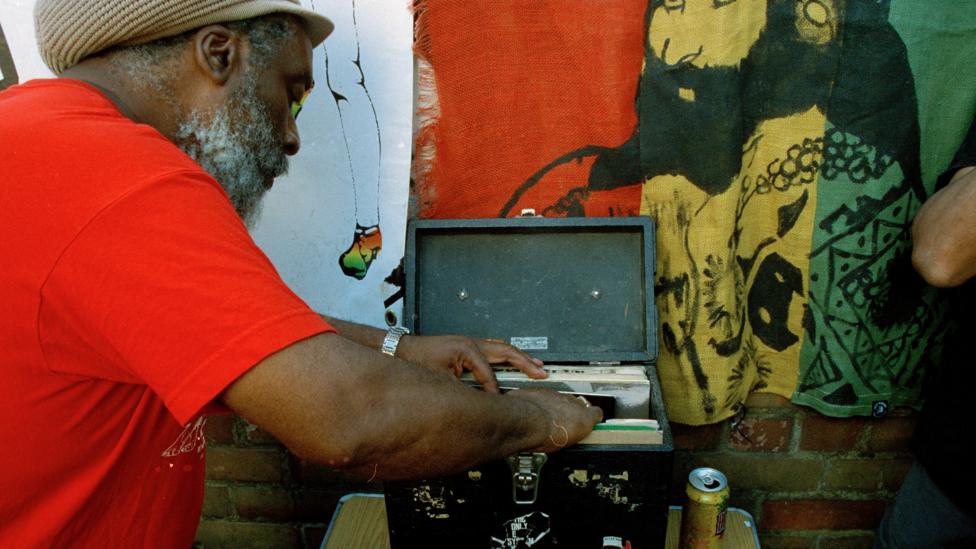

Old-school sound systems like Channel One (here pictured at the 2019 Notting Hill Carnival) continue to fly the flag for dub worldwide (Credit: Eddie Otchere)

From that point on, an entirely new sound opened up – spacious, atmospheric and experimental – that was nothing less than revolutionary. “It’s as big a break from classic recorded music as Picasso’s invention of cubism was from representational painting,” says Joe Muggs, author of Bass, Mid, Tops: An Oral History of Sound System Culture. “It’s common to talk about ‘space’ in dub, but this is not just figurative, it’s literal. This is music aimed at a very specific physical setup of a sound system in a dancehall or yard, [and] the understanding of how the bass, drum patterns and echoes would literally move in space around dancing bodies became very advanced very quickly.” Through Muggs’ work, he has seen how dub’s influence has lived on as an entire mindset. “The lessons about stripping music to bare rhythmic essentials, the physically affecting power of bass and spatial effects, the interplay of repetition and surprise, all fed into every kind of dance music that would follow… You can hear dub in rave, jungle, garage, grime and of course dubstep.”

A physical sensation

Much of dub’s unique power came from being created with outdoor playback at sound systems primarily in mind, rather than radio play or domestic consumption – in short, it was painting on a bigger canvas than most production methods. “The mid range is not so important in Jamaican music,” says Barrow. “Full bass and a very high frequency is. Now when [dub producers/DJs were] playing out in the open air they’d have little treble speakers up in the trees, chipping out. You’d hear that a long, long way away. And as you got nearer you’d start to hear the bass frequencies vibrating through your chest – ‘chest rip’ they call it.”

Nabihah Iqbal is a London-based producer and DJ whose own deeply-textured, electronic music has been strongly informed by her experience and love of dub methods. “In order to fully experience the effect of this music, you need to listen to it on a proper system,” she says. “There’s an astute attention given to the various sonic frequencies by dub music makers and the builders of the sound systems. The way the bass frequencies are accentuated in the music, and the way they are amplified through the speakers makes the music get right inside your body in a way that’s hard to explain… dub has a very physical presence.”

There’s still a strong scene for formal dub worldwide: sound systems like Channel One, Aba Shanti and Young Warrior (son of London sound system legend Jah Shaka) tour constantly, and international festivals Dub Camp (France), International Dub Gathering (Spain), Zion Station (Italy) and Seasplash (Croatia) are thriving. But Joe Muggs points to a wide range of new producers who have taken dub’s ethos, innovations and principles, and transmuted them into something new: “There’s a huge range, from the very obvious like Mala or Congo Natty. who have heavyweight dub at the heart of everything they do, to someone like LCY who sits in a midpoint between arty IDM, serious dancefloor techno, and dub. Om Unit creates incredibly slick, glossy, cinematic pieces but always with a dub pulse. Or Space Afrika who are a young duo from Manchester, but their take on dub is more informed by old techno dudes in Berlin than it is directly by Jamaica.”

Om Unit is one of a host of new producers to transmute dub’s principles into something new, creating cinematic pieces with a dub pulse (Credit: Alamy)

The astonishing surge of creativity around dub waned in the early 1980s when digital production techniques superseded the old analogue mixing desks, and the dancehall era arrived. “Really from there dub became obsolete in Jamaican terms, it wasn’t so important,” says Barrow. “There were still versions on the other side (of singles), still processed with techniques like reverb and delay, but it wasn’t like the old four-track dubs of the golden age, which was really from ’72 through to the early ’80s.”

But dub still endures – both as a musical influence, and also as a musical experience to which people have a deeply personal connection. Many adherents describe its power in almost spiritual terms. “Dub, for me, highlights and defines key moments of my youthful self during a complex era of the 1980s,” says Sister Stellah of the Rastafari Movement UK. “The A-side of a record would awaken me to social commentary… but it was the B-side that gave me a profoundly deeper inner, almost electric, surge of strength. It’s the bassline, it pushes out all negativity… and allows space for magnificent ideas, of hope for my people.”

“I’d describe the music as a feeling,” concurs Iqbal. “It’s music which gets inside you, and you have to give yourself to it. It’s soul-enhancing. It’s something I think about a lot when trying to figure out what I’m doing with my own music. The power of music is beyond our comprehension, but when you experience a dub sound system, you get a little closer to realising how music can affect us spiritually. I feel like all musicians are striving towards this. It’s a constant quest.”

Steve Barrow concludes by summing up just how influential the tidal wave of music and innovation was that emerged from Jamaica in a relatively short period, and how we’re still processing that today. “There’d been remixing before and people experimenting with multi-track recording, but Jamaicans really took it to an entirely new level,” he says. Without those producers and their artistic and technical experiments, almost all electronic music as we know it would now sound different. “Jamaicans made the road and put the signposts up,” says Barrow. “They cut the road and they opened it up.”

Five ultimate dub records

King Tubby – The Roots of Dub (1975): a classic set of Tubby’s dubs of original vocal tracks by the likes of Horace Andy and Johnny Clarke

Augustus Pablo – King Tubby Meets Rockers Uptown (1976): a groundbreaking melodica-heavy album. The title track is perhaps dub’s signature tune.

Keith Hudson – Pick A Dub (1974): an atmospheric, melancholic masterpiece, which crossed over in the UK among the post-punk scene after radio play from John Peel

Lee Scratch Perry – Blackboard Jungle Dub (1973): a contender for being the first dub album released, with Perry mixing his house band The Upsetters

Scientist – Introducing Scientist (1980): the debut album from Hopeton Brown, aka Scientist, a former assistant to King Tubby who ushered in the new generation of producers in 1980 with this supremely technical album.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.