Inclusive and patriotic, with its roots in the radical left, Woody Guthrie’s enduring 1940s folk song offers an expansive vision for all Americans, writes Dorian Lynskey

I

In the 2020 TV series Mrs America, Sarah Paulson plays Alice Macray, a fictional anti-feminist 1970s housewife who is campaigning to thwart the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment. In the penultimate episode, Alice attends the 1977 National Women’s Conference in Houston with a view to sabotaging its platform, but a mysterious white pill melts her defences and sends her on a dream-like journey through the venue. At one point, she wanders into the ‘gay lounge’, where she blissfully sings along to the late Woody Guthrie’s This Land Is Your Land. Elated, she tells one feminist activist that she sings it at home with her kids and the activist responds that a socialist wrote it. Alice laughs incredulously. “Come on, don’t be ridiculous!” When the activist insists that it’s “a Marxist song,” Alice giggles. “Oh no, no, no. It’s patriotic.” The activist smiles. “Exactly.”

It’s a sharp little scene which points out how two political opponents could both relate to Guthrie’s generous vision of the US, but it also raises a crucial question about the significance of a song so famous that it has been described as an ‘alternative national anthem’. Not knowing about the story behind the song may make it universal, but is that at the cost of diluting it?

More like this:

– How The Age of Innocence defined its era

Woody Guthrie lived a classic American life, overflowing with adventure, idealism and tragedy. He was born in Okemah, Oklahoma in 1912. His father Charley was a landlord with political aspirations, but fate did not favour the Guthries. One house fire, in 1919, killed Woody’s older sister Clara. Another, in 1927, sent his mother Nora, who suffered from the degenerative disease Huntington’s chorea, to a mental institution. Charley moved to Pampa, Texas to recover from his burns and asked Woody to join him two years later.

Born in Oklahoma in 1912, Woody Guthrie was a natural entertainer who was drawn to the vagabond life (Credit: Getty Images)

The young Woody was a ravenous autodidact, a natural entertainer and a restless soul. Even though he acquired a wife and child in Pampa, he was drawn to the vagabond life, walking, hitching and boxcar-riding through the American West, and writing songs about the shattered lives he encountered. In California, he became increasingly outraged by the callous treatment given to the economic migrants known as ‘Okies’. His daughter Nora later said that he “learned socialism on the highways of America”. In 1937 he moved to Los Angeles, where he became a minor local celebrity as a protest singer and radio host. After his show was cancelled, he decided to try his luck in New York, arriving in the city in February1940.

It was to be the most important year of Guthrie’s musical life. That spring alone, everything changed. He appeared on stage at New York’s first serious folk music showcase, where he met the folk song collector Alan Lomax and a young singer named Pete Seeger. He began writing what would become his 1943 memoir, Bound for Glory. He worked with Lomax and Seeger on a book of folk protest songs, Hard-Hitting Songs for Hard-Hit People. And he recorded his Lomax-produced debut album, Dust Bowl Ballads.

Guthrie was fortunate to arrive in New York weeks after the release of the film version of John Steinbeck’s 1939 bestseller The Grapes of Wrath. He was seen as a real-life Tom Joad, a genuine Okie straight from the Dust Bowl, with tough, humane songs forged in the crucible of the Great Depression. That pivotal folk concert was called the Grapes of Wrath Evening and Steinbeck himself praised Guthrie in the foreword for Hard-Hitting Songs for Hard-Hit People: “He sings the songs of the people and I suspect that he is, in a way, that people.”

‘Inclusion and equality’

Before any of this, on 23 February, Guthrie sat down in the Hanover House, a fleapit hotel on 43rd Street and 6th Avenue, and wrote six verses of a song he called God Blessed America. As the title made clear, it was a counterblast to a song that had been bugging him: Irving Berlin’s God Bless America. A Russian Jewish immigrant thankful for the safety of his adopted homeland relative to the nightmare engulfing Europe, Berlin framed his song as a ‘prayer’ – for the US and for peace. When the singer Kate Smith debuted it on her radio show on 11 November 1938 (the 20th anniversary of Armistice Day), it was instantly beloved, though not by Guthrie. Sick of hearing Smith’s bombastic recording blasting out of every radio and jukebox he passed by on his way to New York, he was spurred to try writing a different kind of patriotic anthem.

Guthrie was outraged by the plight of economic migrants who were known as ‘Okies’ – captured by the photographer Dorothea Lange (Credit: Getty Images)

Guthrie’s song did not exactly parody Berlin’s but it challenged it. While God Bless America places the country above its humble, grateful populace, Guthrie’s response puts the people first: “This land was made for you and me.” And there’s a lot of more of that land in the song. Whereas Berlin’s brief lyric sketches the US landscape in two lines (“From the mountains to the prairies/ To the oceans white with foam”), Guthrie’s verses encompass forests, valleys, deserts, wheat fields, highways and small towns – the terrain he might have missed while cooped up in a seedy hotel room in a strange city. He ended each line with “God blessed America for me” but seems to have had second thoughts, crossing out each refrain and changing the title to This Land. At the bottom of the page he wrote: “all you can write is what you see.”

Amazingly, Guthrie didn’t understand what he had on his hands. This was no rough draft, demanding heavy revision, yet it was not among the dozens of songs he recorded with Lomax in 1940. In fact, for the next four years he completely ignored it. Only in April 1944, in between stints in the merchant marine, did Guthrie revive This Land is Your Land during an epic recording binge for record executive Moe Asch. That December, he made it the theme tune for his short-lived weekly radio show on New York’s WNEW. “I am out to sing songs that will prove to you that this is your world,” he told his listeners.

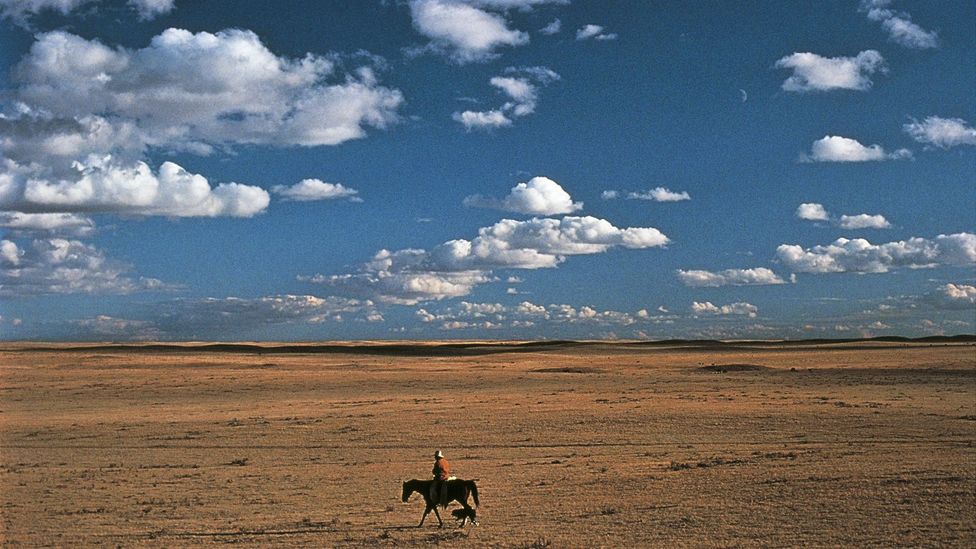

The song’s verses are filled with the US landscape, encompassing forests, valleys, deserts, wheat fields, highways and small towns (Credit: Getty Images)

This Land Is Your Land was finally released (on a compilation album for children) in 1951, albeit in neutered form. Like Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah, it has no single definitive version. Two of the 1940 verses fall in and out of the song. One suggests that the US belongs to everybody, regardless of land ownership:

Was a big high wall there that tried to stop me

A sign was painted said: Private Property.

But on the back side, it didn’t say nothing –

[This land was made for you and me.]

The next verse introduces a note of doubt to the song’s optimistic vision by describing a common scene from the Great Depression:

One bright sunny morning in the shadow of the steeple

By the relief office I saw my people –

As they stood there hungry,

I stood there wondering if

[This land was made for you and me.]

When Guthrie published the lyrics in his 1945 pamphlet Ten of Woody Guthrie’s Songs, he added a final verse, which dispelled that doubt with a defiant reaffirmation of the song’s message:

Nobody living can ever stop me,

As I go walking my freedom highway.

Nobody living can make me turn back

This land was made for you and me.

While every iteration of the song celebrates inclusion and equality, the 1944 recording excludes the relief office verse and the 1951 version misses out both of the radical verses, as does the 1945 pamphlet. In 1950, Guthrie’s publisher Howie Richmond licensed the song for use in school textbooks for just one dollar, which made a song without airplay a viral sensation, and he, too, used the politically sterilised version – understandably, given the rise of McCarthyism. So the version that Mrs America’s Alice Macray would have sung with her children obscured Guthrie’s politics. But what exactly were those politics?

‘Radical patriotism for the masses’

One of the top Google searches for This Land Is Your Land is a complicated question: “Is This Land is Your Land a communist song?” Woody had a quip for that: “I ain’t a communist necessarily, but I been in the red all my life.” While it’s true that he never joined the American Communist Party (CPUSA), during 1938 and 1939 he played many fundraisers and wrote a column for the People’s World newspaper.

For the party, this charismatic, authentic voice from the working-class heartlands was a godsend, because US communists were in a phase of reclaiming patriotism rather than rejecting it. The CPUSA threw its support behind President Roosevelt’s New Deal, claiming: “Communism is 20th Century Americanism.” Guthrie, a quasi-communist who went on to write patriotic songs for Roosevelt’s Bonneville Power Administration, embodied that bridge-building spirit, as did This Land Is Your Land. The song represents something that the left often struggles to achieve: radical patriotism for the masses.

Guthrie – and This Land is Your Land – embodied the bridge-building spirit of US President Roosevelt’s New Deal (Credit: Getty Images)

Already popularised by school textbooks, This Land Is Your Land regained its political bite in the 1960s through the folk revival and the civil rights movement. While recordings by Bing Crosby and Peter, Paul and Mary were abbreviated, Pete Seeger and Guthrie’s son Arlo always performed the radical verses, lest they be forgotten. It helped that Guthrie, no nightingale himself, had written a song that anyone could sing. The robustly cheerful melody (taken from the gospel hymn When the World’s on Fire) was perfect for a protest march, picket line, festival or classroom.

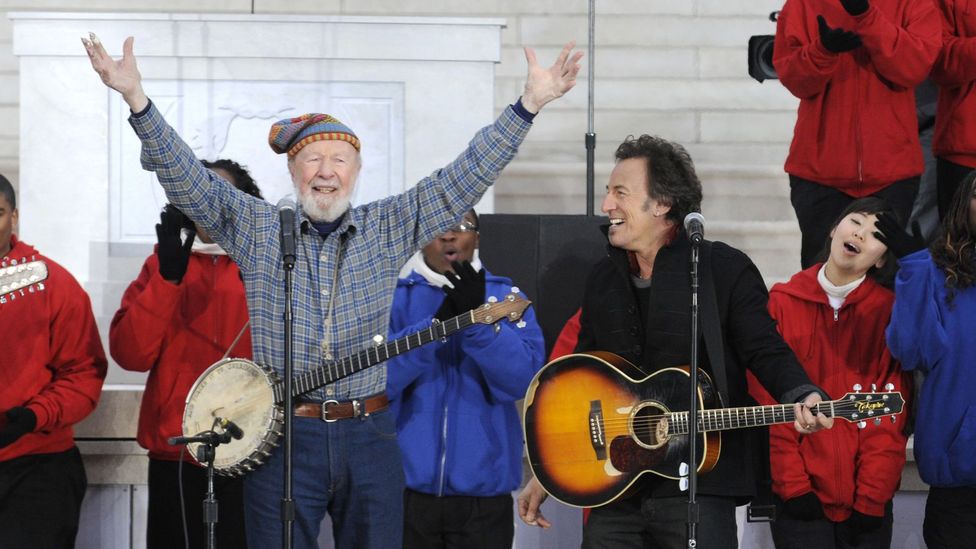

This Land Is Your Land has since become immeasurably famous, woven deep into the fabric of US culture. Bruce Springsteen and Pete Seeger sang it, radical verses and all, at the inauguration of President Barack Obama in 2009. Lady Gaga pointedly combined it with God Bless America in her 2017 Super Bowl performance, while Tom Morello of Rage Against the Machine sang it at the Occupy Wall Street protest camp in 2011. It was sung during the presidential campaigns of Democrats George McGovern in 1972 and Walter Mondale in 1984, as well as that of Mondale’s opponent Ronald Reagan. Bernie Sanders, who recorded his own bewildering reggae version in 1987, made it a mainstay of both his runs for president. It has been parodied in The Simpsons and Tim Robbins’ 1992 satire Bob Roberts, and used to advertise cars and airlines.

A living song

Clearly, it’s a song that anybody can adopt but are there limits to the inclusiveness of “you and me”? Does it exclude anyone? Consider the line of the Declaration of Independence, “All men are created equal,” and what is meant by “all men”. Not women. Not black people, some of whom were held as slaves by the men who wrote that document. Certainly not Native Americans. Does This Land Is Your Land’s democratic message also sin by omission?

Last year, the Native American folk singer Mali Obomsawin argued in Folklife magazine that the left should retire a song that evokes “Manifest Destiny and expansionism” and therefore “anti-Nativism”. “In the context of America, a nation-state built by settler colonialism, Woody Guthrie’s protest anthem exemplifies the particular blind spot that Americans have in regard to Natives: American patriotism erases us, even if it comes in the form of a leftist protest song. Why? Because this land ‘was’ our land.”

Guthrie expert Will Kaufman points out that the singer did occasionally refer to how Native Americans had been bullied and swindled out of their land – indeed, his own father secured some of his farmland that way. Like his hero Walt Whitman, Guthrie aspired to embody all Americans. “My blood beats Spanish and my breath burns Indian and my soul boils negro,” he wrote in an unpublished 1950 poem. Pete Seeger certainly worried about This Land Is Your Land’s apparent blind spot and sometimes sang an additional verse written by Carolyn ‘Cappy’ Israel: “This land is your land, but it once was my land…” Other Native American activists have written their own adaptations.

Pete Seeger and Bruce Springsteen sang This Land is Your Land at President Obama’s inauguration in 2009 (Credit: Getty Images)

This seems to be in the spirit of the song’s expansive patriotism: reclamation rather than rejection. The meaning of “you and me” really depends on who’s singing it. In January 2017, protesters at New York’s JFK airport sang This Land Is Your Land to passengers detained under President Trump’s new travel ban. A few months later, six young immigrant musicians combined elements of their own national anthems with Guthrie’s song to create This Land/Our Land. In the Netflix documentary Knock Down the House, congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez tearfully recalls her late father showing her the sights of Washington DC when she was five years old. “He said, ‘Y’know, this all belongs to us. This is our government. It belongs to us. So all of this stuff is yours.'” The film ends with a righteous soul version of This Land Is Your Land by Sharon Jones and the Dap-Kings: a black woman singing a song by a white man to underscore the words of a woman of Puerto-Rican heritage.

This Land Is Your Land is a living song: a fluid text which can accommodate multiple visions of America and Americans. In the context of the Trump administration, which proposes a narrow, walled-off definition of the US, its radical generosity becomes unignorable and essential. Like the country it celebrates, this song never sits still.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.