The pop pioneer was as remarkable in front of the camera as he was behind a microphone. To mark the fifth anniversary of his death, Laura Studarus talks to those who photographed him.

A

Although a musician by trade, David Bowie has a legacy which is as visual as it is musical – and, as we approach the fifth anniversary of his death on Sunday, that legacy is stronger than ever. The artist’s genre hopscotching, as his catalogue wound through rock, funk, industrial, and avant-garde instrumentals, was always signified by a new image. His evolving style, from the alien-red hair of Ziggy Stardust, to the suited blind man of 2002 album Heathen, is just as much of a definitive statement as his music, creating a loose template for what would be expected of future celebrities.

More like this:

– The false myth of John Lennon

– The world’s best-loved celebrity?

– How pop stars can be truly provocative

Lady Gaga’s character-shifting and costumes were predated by Ziggy and the Thin White Duke – a sartorial tribute that she often acknowledges. Meanwhile, the recent hand-wringing over Harry Styles’s dress on the cover of Vogue regularly neglects the fact that Bowie did it first in 1970, wearing a fetching floral dress designed by Michael Fish on the cover of The Man Who Sold the World. It’s a game of dress-up that validated even his out-of-the-box projects, including playing the role of the Goblin King in cult 1980s fantasy film Labyrinth, narrating Sergei Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf, and performing The Little Drummer Boy with Bing Crosby. He was an outsider who looked the role – let the man make art.

Throughout his career, too, these experimental shifts in his persona were signposted by getting in front of a camera. As documented in the newly published book David Bowie: Icon, which features shots of the star by 25 different photographers, Bowie always understood the power that photography would have in his world. While the images captured during his life are impressive to look back on now, even in the moment, it was clear to many photographers that they were making something special. Here we speak to a few of them to get their reflections on working with a creative legend.

In 2002, Markus Kinko created stunning composite images of Bowie with wild wolves for a GQ magazine shoot (Credit: Markus Kinko)

Markus Klinko

Klinko, who photographed Bowie a handful of times, describes him as an ideal subject – and that wasn’t just because of the musician’s fashion-forward cheek bones. In 2002, when Bowie was unable to schedule a shoot for GQ’s “Man of the Year” award, it was Klinko he trusted to create composite images of him holding a pack of wild wolves at bay. In 2013, based on a desire Klinko had expressed years earlier to direct, Bowie tapped him to helm the video for Valentine’s Day, the fourth single from his album The Next Day. However, Klinko points out that any improvisation he did on set was always based on a well-established idea. Before their first shoot, for the artwork of Heathen, he and Bowie sat together listening to rough mixes of the album prior to entering the studio, just to make sure they were on the same page.

“It was very collaborative, but it started with a very strong idea that he had,” Klinko says. “When you look at the Heathen cover, he’s obviously a blind man with the [whited-out] eyes. It’s a special effect. But even so, he wanted to get this very specific idea of the angle and the eyes being blinded like that. It was a Man Ray kind of inspiration. And the 1940s-style suit, that was something that he wanted very specifically… Sometimes working with other artists that are beautiful and stunning and attractive, they don’t necessarily have the same mindset. They are used to looking good, no matter how. A stylist or myself and the team will decide, this would look really great. Sometimes the publicist will say, don’t go too crazy. But Bowie was very different in that sense.”

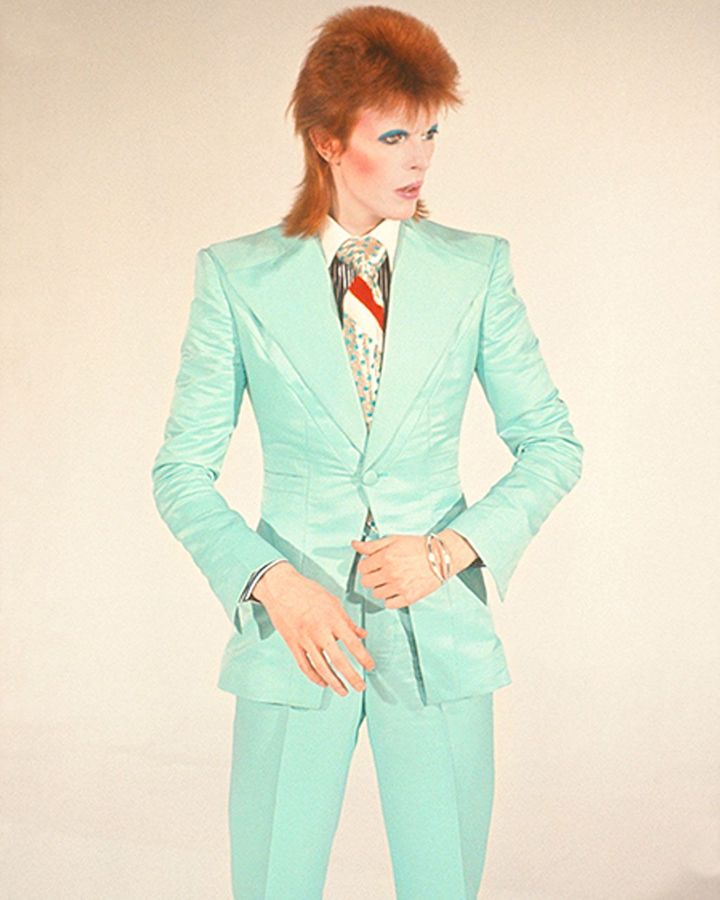

(Credit: Mick Rock 1973, 2021)

Mick Rock

Kinko’s impression of Bowie’s absolute creative determination is echoed by multiple photographers who worked with him. Bowie was clear about his image and how he wanted to present it – but he was smart enough to choose collaborators who could embellish it. Mick Rock was one of his closest collaborators, taking the photos and directing the music videos that define Bowie’s third-eye wearing, Kansai Yamamoto jumpsuit-clad Ziggy years. The two were so close that when Rock was hospitalised due to a heart bypass in 1996, Bowie was one of the people who sent him flowers. When they finally did step into the studio, shooting images of him in Ziggy’s signature red mullet and blue eyeshadow, Rock found it just as much fun as their more candid snaps.

“We did everything between us so we didn’t even have to do a lot of discussion,” he says. “It was because, as you can see from all the pictures, he enjoyed it. He came to play. We didn’t do a lot of preparation, not even for the saxophone shots, which I think back then was the only time I shot him in the studio. And then they showed up in the album package for Pin Ups [his 1973 album and follow-up to 1972’s Ziggy Stardust]. But he was the easiest person in the world, photographs-wise – he couldn’t really take a bad shot.”

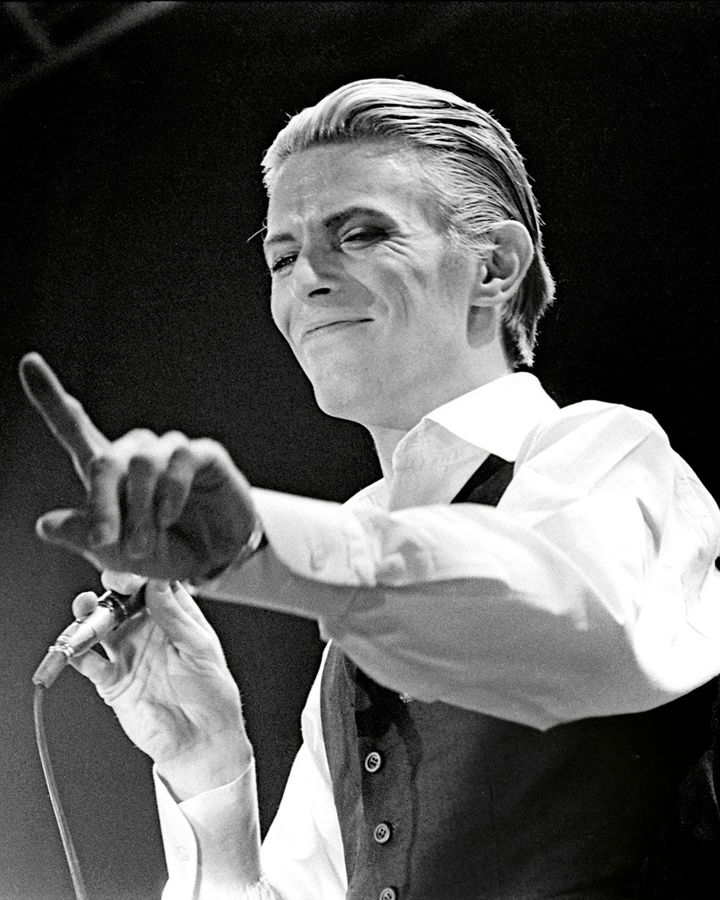

Rock photographer Janet Macoska first snapped Bowie when he appeared in her hometown of Cleveland, Ohio on tour in the mid-1970s (Credit: Janet Macoska)

Janet Macoska

But while Bowie used the ability to tell a story through photographs, Janet Macoska believes that he also understood the effect he had on the people who took them. The Cleveland, Ohio-based photographer spent her teenage years photographing acts who regularly used the city to launch their US tours. When she first saw Bowie perform in 1974, she recalls initially being intimidated by the intensity of his stage presence and two-toned eyes, even though she treasures an ethereal, slightly out-of-focus shot from that first show. But when he returned in 1976, on a tour that didn’t allow photographers, she was given the opportunity to photograph his stage set-up. In return she was allowed to sneak into the show, camera in tow, her rule-breaking “overlooked” by management.

“I popped out every once in a while, to shoot a few photos, but David had two big gorilla guys on stage, one on each side of the stage,” she recalls. “If he saw a camera, he would point at it, and the gorilla guys will come out and take your film. So there I am popping out, and he catches me at it. And he puts his hand out and just waves with a little ‘No you didn’t do that, shame on you!’ And then he smiled and he called off the gorillas. And I shot the whole show! It was like being blessed.”

Macoska’s story is fairly common – at some point, most concert photographers bend venue rules in the name of capturing the perfect shot. However, a second layer to her tale was added in 1995 during Bowie’s tour with Nine Inch Nails, when she was able to present him with a framed photo from that night he saved her from being thrown out. A few weeks later, he responded.

“I got a letter in the mail from Switzerland, and I didn’t know anybody in Switzerland,” she says. “And it was from David thanking me for my gift. ‘Please excuse my tardiness at responding’: It was like [the words of] a little proper British schoolboy, it was wonderful. It was a handwritten letter from David Bowie thanking me for the gift.”

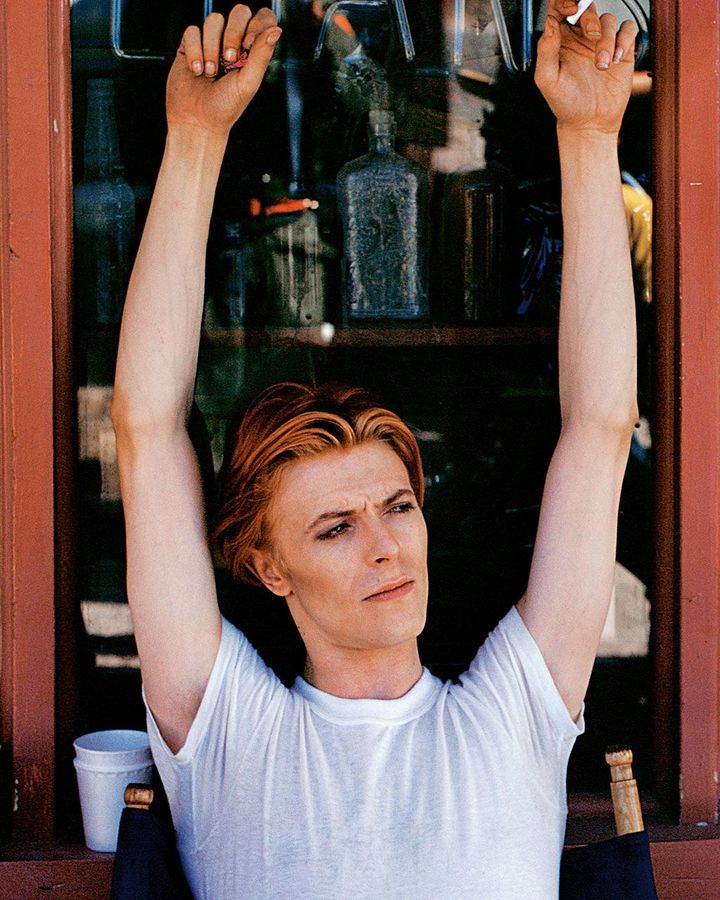

Geoff MacCormack was a childhood friend of Bowie’s who became his tour documentarian from 1973 to 1976, before losing interest in photography (Credit: Geoff MacCormack)

Geoff MacCormack

While many photographers captured the icon, Geoff MacCormack was simply snapping photos of his childhood friend. The schoolmate-turned-supporting band member during the Spiders from Mars and Diamond Dogs tours played many roles in Bowie’s extended circle. These included Los Angeles couch-surfing buddy and the world’s most ill-suited Bowie stand-in on the set of 1976 sci-fi film The Man Who Fell to Earth, taking his place while the crew checked lighting and camera angles, which is a role typically filled by someone who looks more like the star in question. But from 1973 to 1976, also, he became Bowie’s tour documentarian due to an interest in photography that dissipated shortly after: “I’m an imposter, I don’t deserve to be in this book,” he writes in the opening to his Icon section.

His images cover the banalities of tour – Bowie posing in front of various forms of transit, sleeping in tiny train beds, and waiting quietly backstage in full make-up before going on stage. But to hear MacCormack tell it, there was no grand scheme to his work, other than capturing what crossed his lens. “I didn’t say, ‘Oh, I must get up early in the morning. I must not drink too much tonight, so I can get up early in the morning and take a picture,'” he confirms. “It was just a nice picture, peaceful on camera, happenstance.”

MacCormack also laughingly debunks the idea that Bowie was the perfect photographic subject: “I’ve got bits and bobs that he doesn’t look great in, so I won’t use them,” he says. Although his stint as a photographer was brief, he loved the imperfect, documentary-style photos that he took. And so did Bowie.

Five years after his death, Bowie’s stature in pop culture only continues to grow. “I always had a repulsive need to be something more than human,” he once noted. The photos left behind, many pushed into the fine art gallery world due to demand, speak to the success of that life-long art project of otherworldly transformation. Looking at his body of work, it’s difficult to figure out where the icon ends and the man begins. As Klinko points out, that’s exactly the point.

“His last album, Blackstar, the whole way it was launched, the way he died a day later, his whole life in a beautiful way was very artistic and orchestrated,” he says. “He was very aware of what he was doing.”

David Bowie: Icon (ACC Art Books) is out now.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.