The exhilarating protest movement of 1970s Britain, Rock Against Racism, still resonates today. As a new documentary is released, Arwa Haider looks back – and to the future.

P

Protest marches; bigots emboldened in the mainstream; institutional racism and exploitative policies going apparently unchecked… these themes sound distinctly contemporary in 2020, but they’re also undeniably deep-rooted. A new documentary film, White Riot, highlights the 1970s inception of Britain’s Rock Against Racism (RAR) movement, and its ground-breaking carnival event held on 30 April 1978: where a crowd of around 100,000 anti-fascists would march the seven miles from Trafalgar Square in central London to a live concert at Victoria Park in east London, through a stronghold of violent fascist party the National Front.

More like this:

– The birth of Black is Beautiful

– Facing up to Britain’s murky past

– Why are statues so powerful?

Between 1976 and 1982, RAR harnessed creative energies and diverse youth culture, organised live tours, published a highly influential fanzine, TemporaryHoardings, released music, and arguably proved instrumental in trouncing National Front support, at the ballot box and beyond. The movement’s manifesto, written by David Widgery in 1976, was rousing: “We want rebel music, street music. Music that breaks down people’s fear of one another. Crisis music. Now music. Music that knows who the real enemy is. Rock Against Racism. LOVE MUSIC HATE RACISM.”

In 1978 The Clash played at the ground-breaking Rock Against Racism event in east London (Credit: Getty Images)

White Riot celebrates music as a proactive unifying force, and it’s this spirit that definitely resonates now. Director Rubika Shah and co-writer and producer Ed Gibbs began working on the film five years ago, initially struck by footage of The Clash at Victoria Park; White Riot takes its title from the rock band’s spiky 1977 debut single. “I was just blown away by it,” says Shah. “As I dug deeper, I found [RAR] was a bunch of young women and men who had come together in the late ’70s to create this movement in a print room, and that really resonated with me. You don’t often hear stories about music and politics coming out of the UK – especially not positive stories like this.”

The feature-length documentary, which won awards at London, Krakow and Berlin film festivals, builds on an acclaimed 2017 short film by Shah and Gibbs, and involves numerous RAR key players: photographer, activist and agitprop theatre performer Red Saunders; co-founder Roger Huddle; Syd Sheldon and Ruth Gregory (whose vivid photography and design gave Temporary Hoardings its sharp look); Kate Webb (aka Irate Kate) who ran the RAR office and mailed out badges, stickers and publications; smart writers like Lucy Toothpaste (aka Lucy Whitman, whose fanzine articles also gave a platform to themes including feminism and LGBT+ equality). The soundtrack is exhilaratingly multi-genre, through heady live footage (highlights include clips of reggae dons Steel Pulse, and punks X-Ray Spex, led by brilliant young frontwoman Poly Styrene, at Victoria Park; and London Pakistani rockers Alien Kulture; Tom Robinson singing the anthemic Winter Of ’79) as well as contemporary insights.

Poly Styrene, frontwoman of band X-Ray Spex, performed at the event, which attracted a crowd of 100,000 (Credit: Getty Images)

White Riot revisits an era when Britain’s post-war multicultural youth was coming of age, but the hate-filled diatribes of racist politicians such as Conservative MP Enoch Powell and the National Front’s Martin Webster were also disturbingly pervasive. Their white nationalist speeches were even parroted by mainstream entertainers who owed their careers to black inspirations; in 1976, blues rock star Eric Clapton made a notorious outburst at a Birmingham gig, praising Powell and ranting against “foreigners”. Disgusted by this, Saunders, Huddle and peers sent a letter to the New Musical Express, with particular ire for Clapton: “You’re rock music’s biggest colonialist,” it stated. “We want to organise a rank and file movement against the racist poison music… We urge support for Rock Against Racism.”

RAR’s DIY ethos and grass-roots energy felt innately ‘punk’, but its music policy was whole-heartedly broad-ranging, as Huddle tells BBC Culture: “The power of music took us on the anti-Vietnam demonstrations; we all came through the counter-culture. When it came to building RAR, we instinctively went for the music we love and know to be anti-racist – we were energised by punk and reggae, but also soul and psychedelia.”

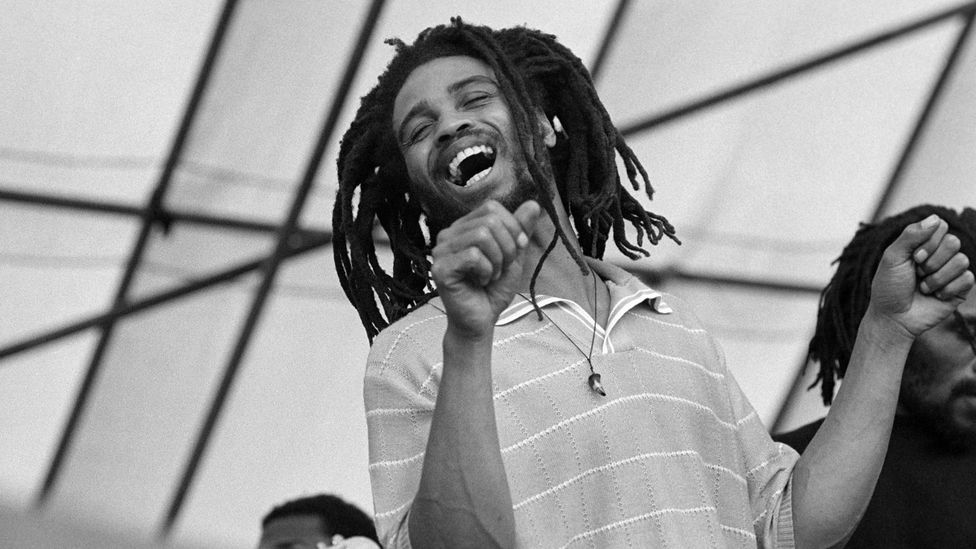

Reggae band Misty in Roots were among the broad range of artists who were part of the movement (Credit: Getty Images)

Now in his 70s, Huddle remains an active anti-racist campaigner. “I’ve never believed that the majority of people are racist,” he says. “I do believe, though, that people pick up a few racist ideas because the society they live in is institutionally racist; a fascist organisation organises around that.”

The inaugural RAR gig took place on 1976, featuring acclaimed British reggae band Matumbi alongside blues singer Carol Grimes. Matumbi’s guitarist was Barbados-born Dennis Bovell, a now legendary artist, writer, producer and DJ, whose credits include work with Janet Kay, The Slits, Linton Kwesi Johnson, The Pop Group, Orange Juice, Viola Wills and Madness. Bovell recalls how Saunders approached him at a south London pub, and explained the plan: to place bands together under the banner of Rock Against Racism: “We thought something like that was due: a coming together of musicians from different genres who were actually against racism,” he says. “So we joined, and we did lots of gigs all over the UK. We went on tour with Ian Dury and The Blockheads, with the Sex and Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll tour.”

Hostile environment

“Unity was necessary for the hostile environment that was around at that time,” says Bovell. “All these National Front marches, and Eric Clapton had made a very damning statement… he’s attempted to withdraw it, but it’s like a thrown stone: once it’s loose, it can’t be retrieved!”

Love Music Hate Racism was founded in 2002 and echoed the spirit of Rock Against Racism (Credit: Getty Images)

As White Riot notes, Bovell himself had experienced serious institutional bigotry; in his early 20s he was falsely imprisoned for “inciting against the police” at a sound-system gig (he won his appeal, and was released after six months in jail.) While we chat, he also recalls a failed “police bust” backstage on the Sex and Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll tour: “None of us had anything that they could arrest us for,” he chuckles. “John Turnbull [Blockheads guitarist] had some henna, and they took that and said: ‘Right, we’re going to analyse this!’.

“We were there for the rock ‘n’ roll – and the reggae, because at the end of every concert, we’d have a big coming together of bands; you’d have rockabilly, reggae, and Ian Dury, who you could say was punk, but he was in a world of his own, with his humour and intelligence.”

For the first time, Bovell’s band were also playing to predominantly white audiences: “You could see that some people’s faces in the crowd were not happy about it – whether a reggae band should be on before Ian Dury,” he says.

RAR shifted perspectives at a time when the mainstream point of view presented was exclusively white; in White Riot, Pauline Black (frontwoman of influential Two-Tone band The Selecter) makes a lucid point that strikes a perennial chord: “RAR was white people finally waking up to the fact that, oh my God, there’s racism here,” she exclaims. “Huh, please! Black people were living it!”

Janelle Monae is among the current generation of musical artists who are outspoken against racism (Credit: Getty Images)

The RAR movement would involve numerous anti-fascist benefit gigs (including a response to the 1979 Southall race riots, where police clashed with anti-National Front protesters, resulting in mass injuries, and the death of teacher Blair Peach), and further carnival events, in London, Manchester and Leeds (where the final all-dayer was held in 1981, including The Specials, Aswad and Misty In Roots). Its ethos (and characteristically direct slogans – such as “Black and White Unite and Fight”) would forge connections and champion equality.

“In the ’70s, we were very much fighting in different battlegrounds; there was the Bradford Asian Youth, and the Southhall Asian Youth, the white punks, Birmingham Afro-Caribbean groups… we tried to bridge that gap, to a certain extent,” says Huddle. “I think we proved a point that the fight against racism is in everybody’s interests. Racism is the most pernicious damage used to divide us; everything is about the continuing campaign against racism – I think you can see it in the Black Lives Matter movement, and the culture that stems from these periods of conscious protest.”

“I fail to see why there is racism at all, given we’re in the 21st Century, and mankind should have progressed beyond racism, but it rears its ugly head now and again, as a reminder that we’ve got to be vigilant,” says Bovell. “All the groups made RAR what it was, there was a big contribution from all genres of music, and it showed the public and the press that there are people who are against racism, and unafraid to say so.”

During her recent video address at the BET Awards, Beyonce dedicated her award to Black Lives Matter protesters (Credit: Getty Images)

The legacy of RAR is multi-stranded; it fuelled collaborative culture, yet by the mid-’80s, commercial acts seemed increasingly reluctant to appear “political”, and the Labour party-affiliated movement Red Wedge was derided in the pop press (this history is explored further in Daniel Rachel’s excellent book Walls Come Tumbling Down). In contrast, contemporary collective Love Music Hate Racism (LMHR) was founded in 2002, named in homage to the late David Widgery’s RAR slogan, and echoing its spirit.

“LMHR is the spiritual and organisational offspring of RAR,” says Ira Sylvester, one of LMHR’s current national organisers. “Both organisations were of their time and both evolved over time. We are fighting to protect multiculturalism, to celebrate difference, and say that what you bring to the party matters than the colour of your skin, your gender or where you are born.”

As Sylvester argues, the bigotry that RAR made a stand against hasn’t dissipated; it may have shape-shifted and chosen new targets, while austerity and unemployment is still used to create divisions. “The fascists keep trying to march on the streets and institutional racism remains a massive issue, so the fight goes on – and so does the belief that having fun while fighting injustice is the best way to succeed,” he says.

The new documentary film White Riot takes its name from the explosive 1977 single by The Clash (Credit: Syd Sheldon/ White Riot)

Certainly, White Riot does not feel like a hazy period piece; its archive footage is vivid-hued and bristles with adrenalin, and its most galvanising moments include the many ordinary Britons who travelled to the Victoria Park carnival (42 coaches came from Scottish city Glasgow alone) to march against racism. It brings us, hopefully, to a new generation of outspoken artists: musical heroes like Stormzy or Dave denouncing racist injustice on prime-time TV; MIA’s thrillingly polemical rhythms or Janelle Monae’s elegant fury; Beyonce’s recent video address at the BET Awards, where she dedicated her Humanitarian Award to BLM protesters, exhorting viewers to “continue to change and dismantle a racist and unequal system”.

It is infinitely more than an isolated ‘moment’ or fleeting gesture; it reminds us of the necessity of connecting and revaluating histories, along with the power of the here and now. As Bovell says: “This Rock Against Racism thing went around the whole globe; a lot of people came to support in France, Germany, Japan. We tried to combat the racial tension of the world, not just where we were. It was a good seed planted.”

White Riot is being screened around the UK by Modern Films.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.