An exhibition in Amsterdam celebrates the work of a nanny who has come to be recognised as a master photographer, writes Andrew Dickson.

I

It was the kind of discovery that curators dream about during slow days at the museum. In 2007, a Chicago history buff named John Maloof bought a box full of negatives on a whim at auction for $400. Sorting through them, he realised he’d stumbled across something astonishing: charismatic, crisply composed pictures of the city in the 1950s and 60s, which ranked with the best US street photographs of the period. Not only had none of these images been seen before, no one had a clue who had taken them.

More like this:

– The battle to save Beirut’s heritage

– The images that fought Fascism

– Remarkable photos of people in nature

Maloof managed to track down more work by the same hand – eventually amassing an archive of up to 100,000 negatives and some 3,000 prints, plus box upon box of film rolls, audio interviews, receipts, letters and countless personal effects. After further sleuthing, he finally managed to give the anonymous photographer an identity: she was a former professional carer named Vivian Maier, who had since died, and who had kept her images – and her remarkable talent – all but hidden from everyone she knew.

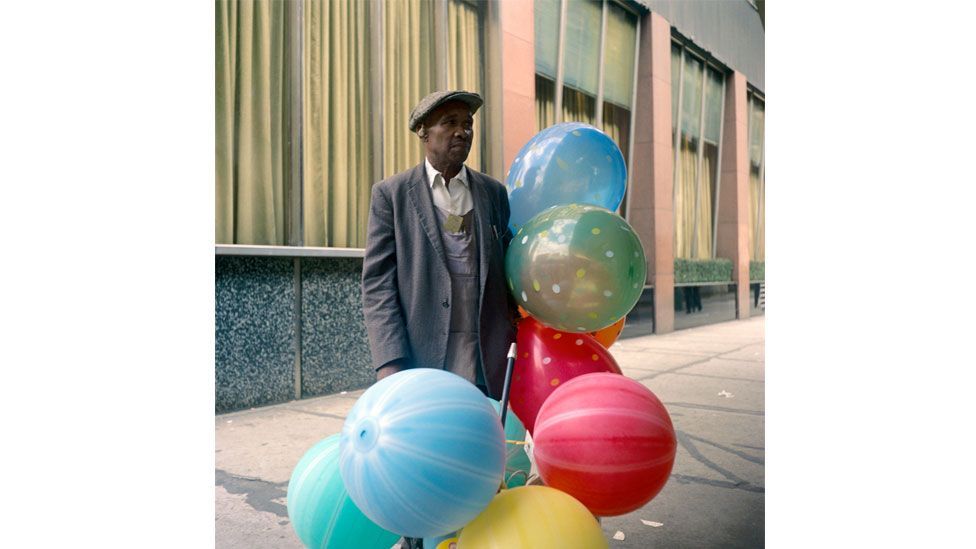

Chicago, 1971 (Credit: Estate of Vivian Maier, Courtesy Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York)

Although she assiduously avoided the limelight during her lifetime, over the last decade Maier has become one of the biggest names in photography. A Flickr showcase of her archive attracted vast numbers of visitors, and the physical exhibitions that followed in Europe and North America were mobbed. In 2013, she became the subject of an Oscar-nominated documentary, which retold Maloof’s efforts to locate traces of the nanny-with-a-secret-passion-for-photography. With a sad and somehow American inevitability, Maier even became the subject of a bitter posthumous legal battle over who owned the rights to show and profit from her work. The artist herself, who died nearly penniless after selling everything she had, was, of course, not around to protest – or benefit.

The woman behind the myth

Such has been the fuss and farrago that it’s often been hard to see Maier in her own terms. The mythology that has crept up around her like bindweed – the seductive fairytale of the self-taught outsider genius, the eccentric recluse who photographed like Robert Frank or Garry Winogrand yet refused to show anyone her work – has a way of getting in the way of the pictures.

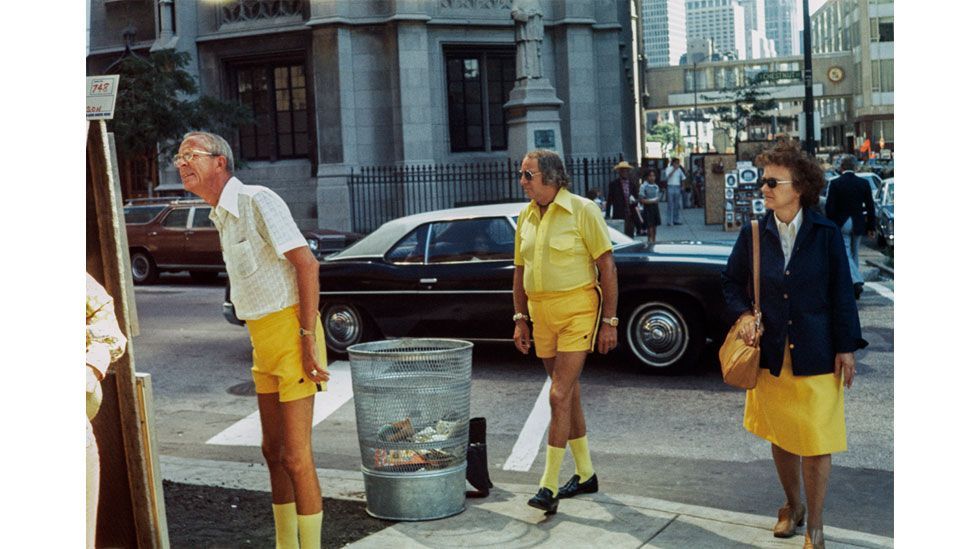

Chicago, 1975 (Credit: Estate of Vivian Maier, Courtesy Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York)

But an exhibition running this summer at the Foam photography museum in Amsterdam aims to move her into a different light. Devoted to a lesser-known part of Maier’s output, her colour photographs, it brings together 60 images, mostly taken in Chicago and the surrounding area from the mid-1950s to 1986, when Maier was in her late 50s. More than that, it gives us the opportunity to look afresh at this most unusual and intriguing of image-makers. What kind of photographer was Maier, really? What kind of artist?

As I roam through the galleries via Zoom in the company of Foam’s director, Marcel Feil, one answer that occurs to me is: many different kinds of artists, all at once. “She can kind of do anything,” says Feil, holding up his phone camera to show me a shot of a man’s jacket sagging on a coat stand, taken in 1962. Despite the banality of the image, it has an eerie pathos, hard to unravel. “It’s pretty astonishing what she can do,” Feil adds.

One surprise of the show, particularly if you mainly know Maier as a street photographer, is how on colour film she shows herself capable of much more. To be sure, the pictures are undeniably her: there’s the same sly, sometimes macabre taste for the strangeness and delight of the American city, and the same warmly sympathetic images of children (hardly surprising, given her day job). You also find the same mischievous eye for people who don’t quite fit in – another theme that may have had personal resonance. One frame shows a woman in Milwaukee in 1967, splendidly attired in fur stole, sunglasses and bonnet like a Hollywood star from the silent era. She seems to be living in a different reality – a far grander and nobler one – than the humdrum urban scene that surrounds her.

Santa Fe railroad, Chicago, 1959 (Credit: Estate of Vivian Maier, Courtesy Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York)

“She’s a quiet, careful analyser,” says Claartje van Dijk, Foam’s head of exhibitions, who curated the show. “She really sees what’s happening beyond the street scene, what’s occurring in the moment.”

But as well as street shots, there are abstract pictures, still lives, images of found objects. Some are knowingly surreal; more often, they’re homages to the casual beauty of the everyday. One picture offers us a pile of broken glass on a flight of wooden steps, the handrail casting a jagged abstract pattern in the stark winter sun: accidental abstraction. Elsewhere, a small crowd of women’s hats lies upside-down on the floor, their jewel-like colours glowing in the afternoon light – presumably they’re Maier’s own, though as usual there’s no clue.

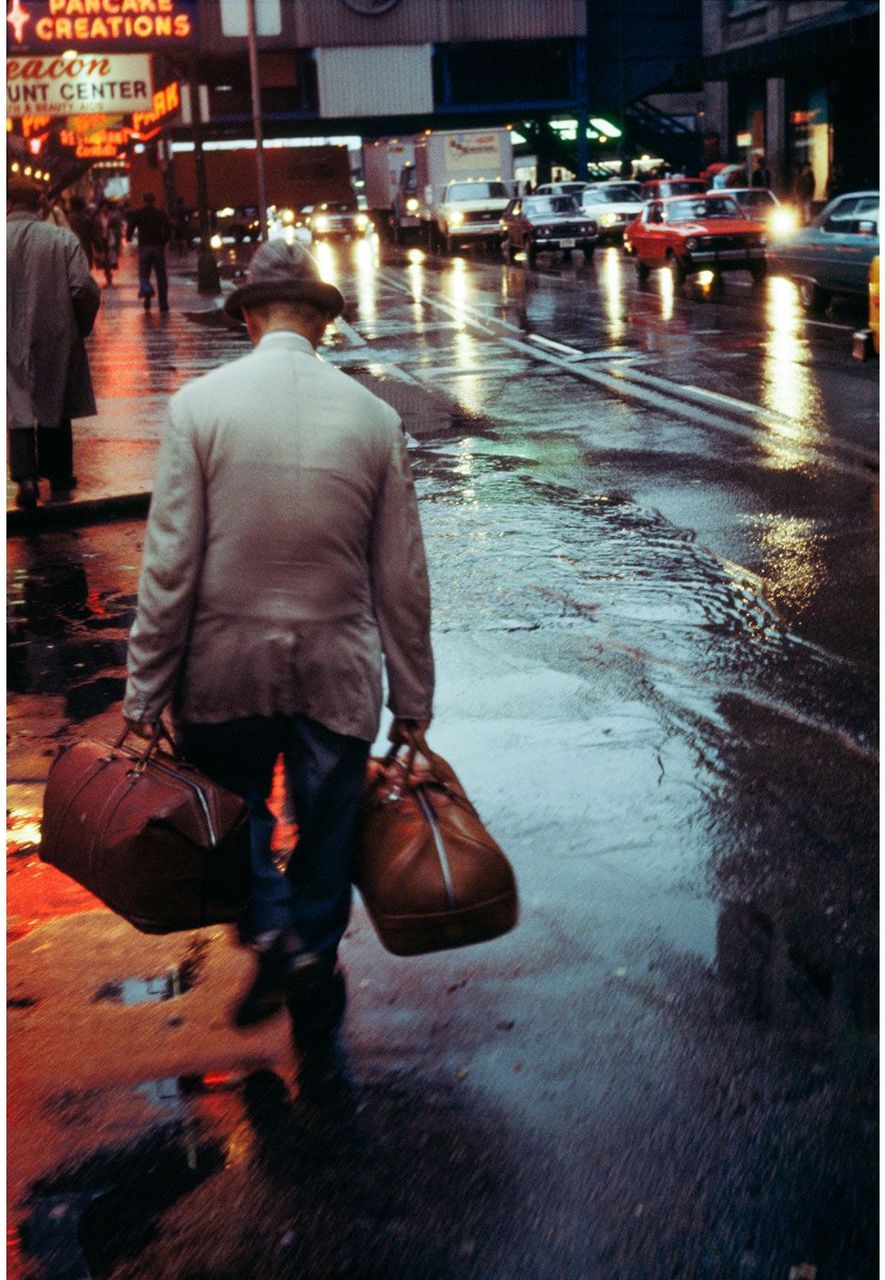

Chicago, 1978 (Credit: Estate of Vivian Maier, Courtesy Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York)

In another picture, she captures a fancy-looking, open-top car by the side of the road, a clump of flowers climbing out of the back seat (the driver must have stopped at a florist, though the plants look as if they’ve taken root). You instinctively think of photographers such as William Eggleston and Stephen Shore, whose gothic images of Americana in the 1970s made critics realise that colour photography could be high art. Then you discover that Maier was making these images more than a decade earlier.

“She was a real pioneer,” says Van Dijk. “Really we should be comparing those male photographers to her.”

Location Unknown, 1960 (Credit: Estate of Vivian Maier, Courtesy Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York)

One of the most lustrous images on display shows a man eating a packed lunch somewhere outside. Maier crops out his head; all we really see is a hairy arm, the paunch of a shirt and some undistinguished trousers. He looks like the most average of average Joes, were it not for the luscious array of sandwiches and fruit in a cardboard shoebox next to him. While for these images Maier was using a small, light 35mm Leica camera – much easier to operate than the twin-lens, medium-format Rolleiflex she usually dragged around – shooting in colour seems to have encouraged her to linger on such moments. Though it’s technically a street photograph, this image looks as abundant and beautifully composed as a 17th-Century Dutch still life.

“She’s really looking at texture and colour,” agrees Van Dijk. “Not just what’s going on on the street, but the framing and composition. The pattern of a woman’s dress, the way someone is standing, horizontal and vertical lines – everything.”

Chicago, 1962 (Credit: Estate of Vivian Maier, Courtesy Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York)

Self-portraits are one of Maier’s most tantalising obsessions. As well as her fondness for capturing faintly ghoulish pictures of dismembered mannequins, Maier clearly enjoyed turning her lens on her own body, catching herself if by accident in a mirror or shop window (though you sense it’s never accidental) or posing in a bathroom, while having her hair cut, silhouetted against a garden fence – anywhere that could generate an interesting image.

Self Portrait, Chicagoland, 1975 (Credit: Estate of Vivian Maier, Courtesy Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York)

Even in the posed pictures, Maier’s expression is invariably impossible to decipher: she seems to be daring us to guess exactly what she’s thinking – or, perhaps, daring herself. These games of catch-me-if-you-can seem to give her quiet pleasure. She took one particularly droll photograph on a station platform in Chicago in July 1978, facing towards a line of movie posters pasted to the wall. All we see of her is a hat-wearing, hand-bag-clutching shadow looming at the left of the frame: far more menacing than the advert for Jaws nearby. It’s as if Mary Poppins were auditioning for a role as a serial killer.

Hiding in plain sight

Speaking of nannies, certain things have become clearer since Maier’s rediscovery, many of which disturb the foundations of the myths that have become attached to her. Over the years, more and more of her many photographs have been publicly available, giving a clear sense of how carefully she framed her images and how painstakingly she worked at her craft. Researchers combing through her archive have demonstrated that she was a far worldlier – and more politically engaged – person than we might expect, given how reclusive those who knew her remember.

Pamela Bannos’s careful, illuminating biography, published in 2017, suggests that while Maier didn’t have any professional training that we know of, she visited exhibitions and had a sharp eye for other people’s image-making, as revealed by the newspapers she obsessively collected (newspapers and posters often crop up in her own photographs). Yes, the Maier who emerges from this account was somewhat eccentric – she appears to have struggled with mental illness later in life – but was also powerfully aware of her own talent.

Chicago, 1977 (Credit: Estate of Vivian Maier, Courtesy Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York)

Even her unwillingness to show her work is perhaps easier to comprehend than we’d like to admit. Say if she’d managed to find the money to get her pictures properly printed, and the art-world connections to get them exhibited, would she have been taken seriously? Bannos reports that Maier told a friend that “if she had not kept her images secret, people would have stolen or misused them”. Given what happened after she died, that hardly seems paranoid.

The question that follows is obvious for any curator: should Maier’s work even be shown now? While appreciating the complexities of the issue, Feil argues the answer is yes. “When I look at the way she made her images, the consistency and the craft of them, I think the results were made to be seen. I do think that.”

Van Dijk points out that Maier maintained a correspondence with a photography studio in France, and discussed printing her images as postcards – evidence that she did have an interest in them being seen by others, at least when she had the money. But ultimately her intentions remain a mystery: “There’s something difficult about that. The world is happy to see the work, but would it have been more respectful to her to leave it where it was? I honestly don’t know.”

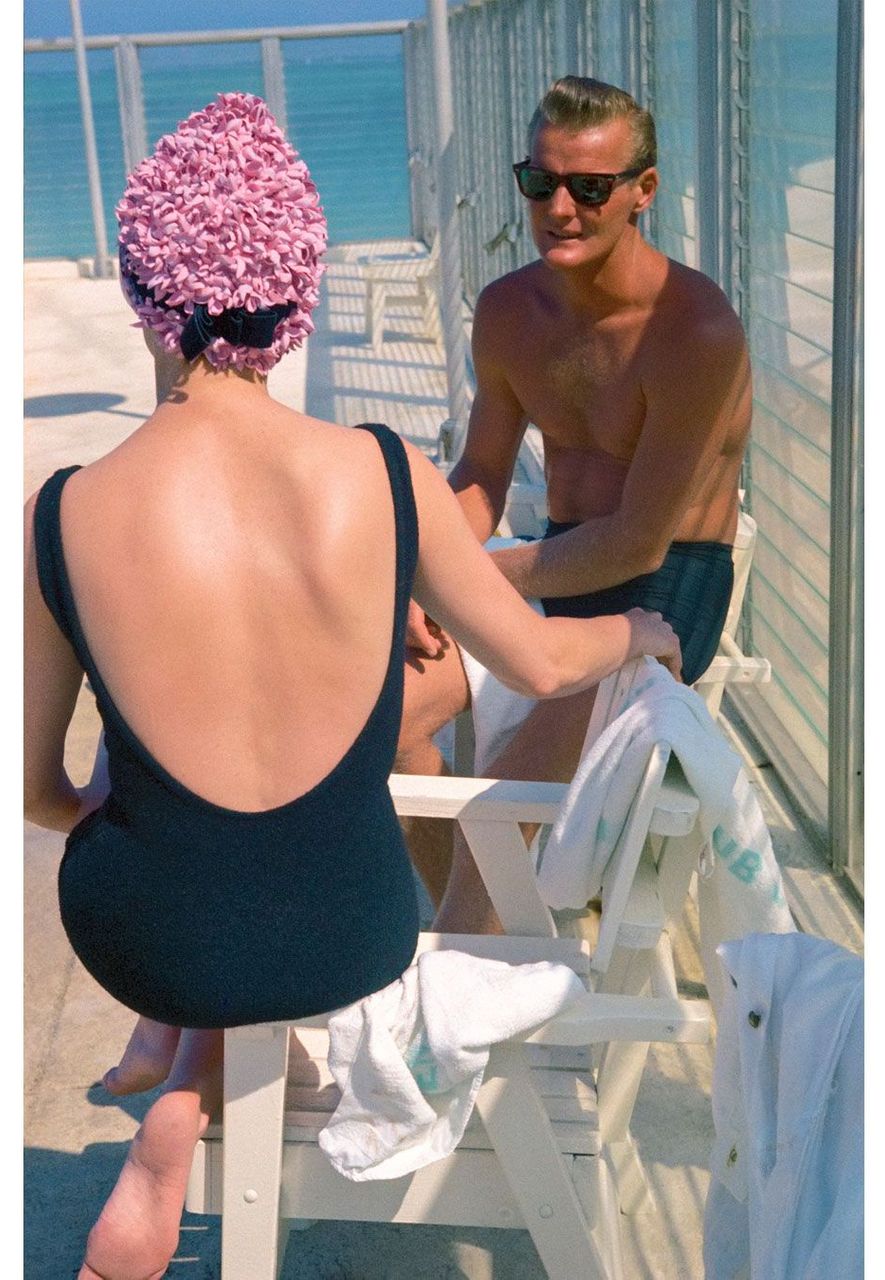

Fontainebleau Hotel, Miami, 1960 (Credit: Estate of Vivian Maier, Courtesy Maloof Collection and Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York)

One thing does seem inarguable. Instead of regarding her as a nanny who happened to take great snapshots, we should recognise, once and for all, that Maier was the opposite: a photographer who chose to support herself financially, and develop her art, by being paid to look after other people’s children. She made the most of what being a full-time carer could offer – particularly the freedom to roam the streets for hours at a time, kids in tow, documenting whatever or whoever she found on the way. For a roving street photographer, a nanny (that most marginal and unthreatening of roles) was clearly a useful disguise.

Perhaps, indeed, even all her hoarding – the newspapers, the receipts, the ticket stubs, the indecipherable scribbled notes – were a kind of artistic process, a way of recording and registering her existence, much as Andy Warhol did with his time capsules (except, of course, that with Warhol we have no issue with regarding what he did as art).

“It was a means to an end, I have no doubt about that,” says Van Dijk, pointing out that we also have no difficulty in regarding male photographers who supported themselves by non-artistic employment as artists. “She was an artist, I really believe that.”

However much more is discovered about Maier – we are, perhaps, still only starting to get to grips with her – perhaps the truth is that she is harder to pin down, far more elusive, than we have yet realised.

“There’s no need to compare her to anyone else,” says Van Dijk. “She is very much herself.”

Vivian Maier: Works in Colour is at Foam Amsterdam until 13 September.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.