The gonzo chefs who are TV’s ultimate pleasure-seekers

In our latest essay in which a critic reflects on culture that brings them joy, Laura Martin pays tribute to the maverick cooks who have been her lifeline to the world during lockdown.

I

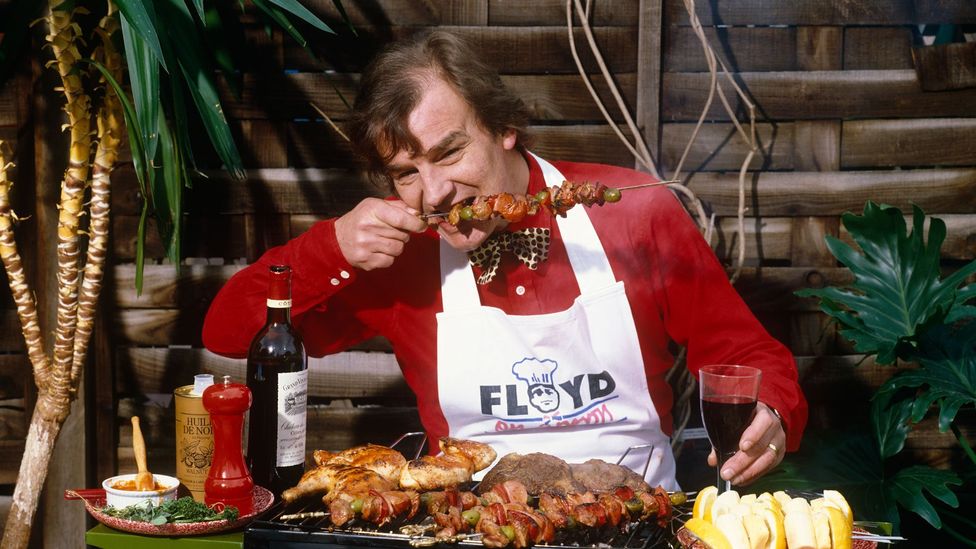

It’s 10am and the chef Keith Floyd is getting sloshed, again. Perched on a hay cart on the side of a Provencal road with a Frenchman called Christian, he’s extolling the virtues of a “Vermeer painting” of a spread: home-cured ham, tomatoes, truffles, pork terrine and a platter of cheese. “A votre sante!” he cheers, clinking his glass of breakfast wine with his new friend.

More like this:

– The most joyful books ever written

– The cartoon with the meaning of life

– Why Marvel films have helped me grieve

I’m not quite sure how or why an Eight-year-old girl became so enamoured with a TV show featuring a globe-trotting, bow-tied, 45-year-old bon viveur. But I can definitely attribute it to me, still aged eight, demanding to take over our family kitchen for a week to make a different global cuisine dinner each night, even diligently tapping out my ‘Round The World’ menu on my parents’ typewriter. Had you stuck your head into the kitchen while I cooked up my rudimentary spaghetti bolognese, you would have also found me talking to an imaginary camera, just like my culinary hero.

During the 1980s and 1990s, chef Keith Floyd offered millions of British people the chance to live vicariously with his madcap culinary travelogues (Credit: Alamy)

Now three decades on, and in lockdown, I find myself once again feasting on cookery TV shows, among them Floyd’s now very retro back catalogue.

Is watching a natural-born enthusiast visit the best restaurants around the world and cook up gourmet dishes tantamount to self-torture right now? Quite possibly, but it’s also providing a much-needed dose of escapism.

The first rock ‘n’ roll chef

I suspect it was the same for my parents, who – like millions of others in the UK – avidly watched the 20-odd series of Floyd’s cooking shows in the late ’80s and ’90s. Through his often steamed-up camera lens, we travelled the world with him, from France and Italy through to the US, Australia and Asia, as he gallivanted about as excitably as a school boy let loose on a class trip. For a generation who perhaps went on one European holiday a year, and who ate out at restaurants rarely and only on very special occasions, his foodie travelogue exploits offered them a chance to live vicariously. Growing up, my dad was known to sport a Panama hat like Floyd’s on holiday, as well as humming his signature theme tune, Walzinblack by The Stranglers, while he cooked, neither of which was just coincidence, I think.

Floyd first burst on to the BBC in 1984 with Floyd on Fish, a slapdash series in which he charmingly ad-libbed his way through Cornwall, cooking up dishes then little-known in the UK like the French seafood stew bouillabaisse, while having a trademark ‘quick slurp’ of wine while he did so. “So, my little gastronauts,” he’d start. “Have I got a treat for you today!” He’d set pans on fire, call guests by the wrong name (a young Rick Stein is introduced as “Nick”) and generally exude a big chaotic energy while somehow always holding it together enough to create a glorious final dish. It was an alchemy of mayhem in a makeshift kitchen, led by a man who didn’t even regard himself as a chef, just a cook who happened to be in the right place at the right time.

Back in Britain in the late 1980s, Floyd’s shows weren’t like any other cooking on television. From the almost grim seriousness of early MasterChef (“we’ve deliberated, cogitated and digested,” Loyd Grossman would drawl each episode, sending me running for a dictionary) to the prim, teacher-like Delia Smith boiling an egg as if it were a science experiment, food based-programmes were less a rollicking Bacchanalian feast, and more instructional home economics videos.

The Two Fat Ladies, aka Clarissa Dickson-Wright and Jennifer Paterson, roared around the UK on a motorbike and sidecar, and like Floyd brought verve to food TV (Credit: Alamy)

Just as rock ‘n’ roll music shocked a sedate society into colour and verve in the 1960s, Floyd and other unruly cooking peers (like the duo that were The Two Fat Ladies, aka Clarissa Dickson-Wright and Jennifer Paterson, who roared around the UK on a motorbike and sidecar) led the way for a cultural overhaul in how food was portrayed on TV.

A riot of personality

Cooking went gonzo. Gone were stilted monologues to camera and the idea that televisual cuisine simply needed to involve a camera on a hob and a recipe read aloud. Instead, chefs with madcap personalities were let loose from their kitchens and sent on location, free to blunder and bluster their way through almost anarchic scenes, as they wrangled their meat and veg. They nattered away naturally and knocked up sensational dishes while blowing away the stuffy mystique of ‘fine dining’, making their high-end food seem accessible to people like us at home.

Prior to this revolution, there had been very little on British television that really illustrated the fun of cooking with beautiful produce, and that didn’t display the resulting dishes as cold artworks on a studio counter. Shows post-Floyd followed his lead in serving up their creations in a homely style, to a table of appreciative friends – a trope used often from this point onwards by chefs like Jamie Oliver and Nigella Lawson (despite them staging such scenes with hired actors, as it later turned out).

“Throw a little bit in there,” these new cooks instructed us, or “a nice, big slosh of that”, as precise recipe measurements went out of the window. It showed us our efforts didn’t have to be perfect, but that the cooking could be as thrilling as the eating.

Floyd also became the inspiration for many ‘chef on their travels’ series and it’s now become a standard pitch for any high-profile culinary type. Many of them are dismal, sadly: obvious, clunky and repeating tired national stereotypes. But one chef who turned the culinary travelogue into an art form – and who has again provided me with sensory solace over the years – was the New York chef Anthony Bourdain.

Anthony Bourdain mixed a sometimes curmudgeonly front with a passionate investment in other cultures, other humans, their lives and their food (Credit: Alamy)

In 2002, riding high from his best-selling book, Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly, he started A Cook’s Tour on America’s Food Network, in which he made it his mission to explore the food scene of pretty much every country on the planet. This early series sometimes relied a little too heavily on a repetitive ‘man drinks beer and eats fried meat in hot country’ formula, but by the time he had graduated to No Reservations (currently streaming on Amazon Prime) or Parts Unknown (available on Amazon Prime and Netflix), he used food as a starting point to explain the vast histories and cultures of places.

I can easily spend hours absorbed in his series, but even more so now, as they give me a taste of two currently forbidden joys: travel and dining out. When you stumble upon a gem of an episode, like those where he visits South Korea or Tokyo or Hanoi, you get to watch Bourdain falling in love in real time with a place, and somehow, he manages to make you feel nostalgia for somewhere you’ve never visited.

Bourdain was heavily influenced by Floyd’s ideas of food and presenting, where the best stories are found by pulling up a chair with locals and eating their delicacies. “I’ll try anything and risk everything,” he once said. “I have nothing to lose.” Once again, there’s a realness to his work as the camera is kept rolling when things don’t go exactly to plan. Like my other favourite chefs, he tells us exactly what he’s thinking, and all of his cynical, rough-around-the edges comments are left in the edit. For all his curmudgeonly front, however, his passionate investment in other cultures, other humans, their lives and their food shines through. When Bourdain died in June 2018, his former dinner guest at a noodle shop in Vietnam, Barack Obama, tweeted: “He taught us about food – but more importantly, about its ability to bring us together. To make us a little less afraid of the unknown.”

The new mavericks

Of course, both Floyd and Bourdain’s shows, centred as they are on white men, now raise the issue of who gets to tell global food stories. Watching them back again, the privilege of these men who travelled the world, often appropriating other nations’ cultures, is ever more glaring – even as, depressingly, so little has changed. Thirty years on from Floyd’s heyday, food TV – and food media in general – is still shamefully predominantly white, and, among other things, there’s a lot of work to be done in increasing the diversity of on-screen chefs.

Chef David Chang’s series Ugly Delicious is an enlightening and often heart-warming watch – but never takes food too seriously (Credit: Netflix)

What’s gratifying, however, is that the spirit of gonzo cheffing today is perhaps best represented by two BIPOC cooks, David Chang and Samin Nosrat, who I have also been turning back to during lockdown.

Since 2018, the affable Chang – chef owner of the Momofuku, Fuku and Milk Bar restaurants across the world – has presented his own Netflix series, Ugly Delicious, where he takes one particular dish, such as pizza or fried rice or tacos, and travels the globe, exploring the history of the food and what it means to different people in different cultures. There are no-holds-barred roundtables about food as identity or emotional memory alongside bright memes and social media clips flashed up on screen, and Chang often hands the baton over to other people he deems more qualified to chat about the ingredient or issue than himself.

Some are deeply personal visual essays, such as the second season episode Kids Menu, which documents Chang’s wife Grace Seo Chang’s pregnancy and labour, and sees him knowingly upend sexist norms by asking male chefs how they juggle having children while working in an 80-hour-a-week industry.

The series is an informal, enlightening and often heart-warming watch – but that’s not to say it’s not funny. In episode seven of series one, Chang pokes fun at the often po-faced grandeur of the streaming site’s other food hit, Chef’s Table, in a skit that ends up with him chopping off his thumb and spraying blood all over the displayed plate. Like many of his best TV predecessors, Chang knows the cardinal rule of never taking food too seriously.

When it comes to showcasing the purest joy that food brings to people, meanwhile, no-one does it better than Nosrat. The Californian chef began her career at the world-renowned restaurant Chez Panisse, before publishing her award-winning cookbook Salt Fat Acid Heat in 2017. A year later, she landed her own television series of the same name on Netflix, which has rightfully become a cult hit.

Samin Nosrat’s radiant enthusiasm and spontaneity on camera makes her an electric screen presence (Credit: Netflix)

“I’ve spent my entire life in pursuit of flavour,” she says in the opening episode, which becomes ever more apparent as the passionate host travels to Japan, Mexico, and Italy, as well as returning to her home turf of California, in exploration of the different spectrums of taste. What strikes you throughout is Nosrat’s radiant enthusiasm, as she launches into the food placed before her, eyes often closed when chewing, soaking in the sensation, before breaking out into a broad smile and saying: “WOW. Wow.” As I polish off my third bowl of cereal of the day on my sofa, I’ve never had food envy more than when watching Nosrat eat, though seeing her on screen has given me a much needed serotonin hit over the past few months.

Nosrat’s spontaneity on camera is another other key ingredient. In the Acid episode, while testing spicy salsas, she laughs so hard she can hardly get her words out. “Oh my god, that’s the spiciest… so spicy… I’m gonna cry, that was too stupid of me,” she exclaims, in hysterics, as her face reddens. Then she takes a swig of her beer, cheers her dining companion and takes another bite. (In an often male-centric industry, it’s also great to see how she champions other women throughout the series, whether going to the market with a Mexican home cook, or trying sushi with her chef friend Yuri on a Japanese island.)

For all their different styles and passions, these four maverick chefs each approach their work with bags of humour and heart, which is why revisiting them has been such a comfort right now for this armchair traveller. Eating is such a visceral activity, and there aren’t many people who can actually convey the pleasures of this on screen.

Ultimately, seeing the world through the lens of people who savour every single mouthful, like Floyd, Bourdain, Chang and Nosrat, makes me feel a little more optimistic for the future. Once lockdown is over, I can’t wait to dig into it all again. Just like Floyd, maybe I’ll celebrate with some breakfast wine, too.

Floyd on France in currently streaming on BBC iPlayer in the UK. No Reservations is available on Amazon Prime, and Parts Unknown is available on Netflix in the UK and Amazon Prime in the US. Ugly Delicious and Salt Fat Acid Heat are both available on Netflix.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.