A satellite that will be critical to understanding of climate change will launch on Saturday from California.

Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich will become the primary means of measuring the shape of the world’s oceans.

Its data will track not only sea-level rise but reveal how the great mass of waters are moving around the globe.

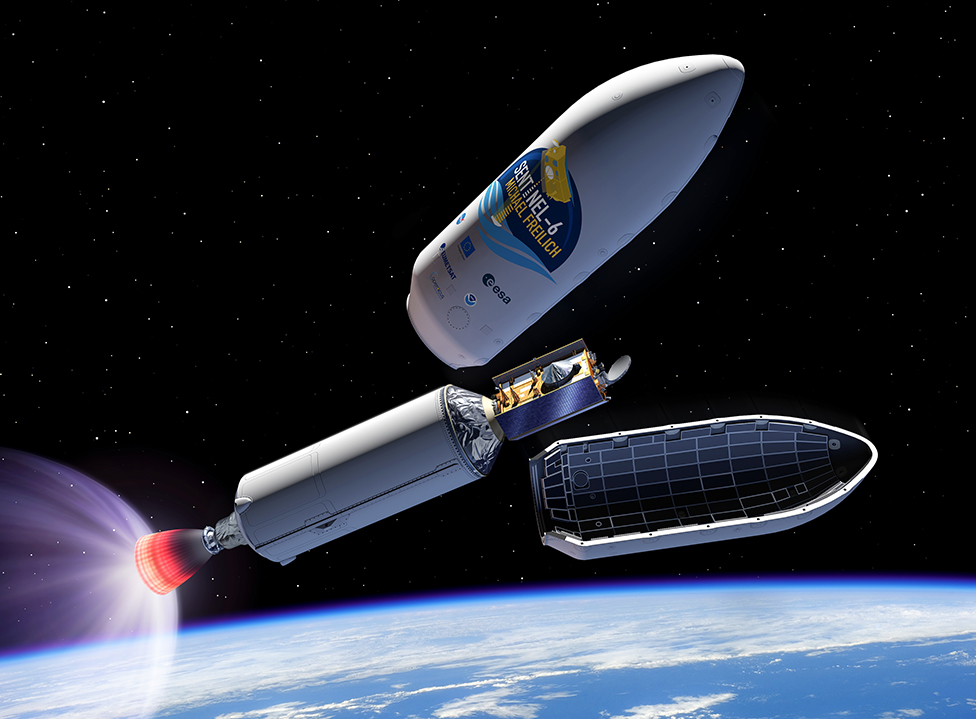

Looking somewhat like a dog kennel, the sophisticated 1.3-tonne satellite is due to lift off from the Vandenberg base at 09:17 local time (17:17 GMT).

The Sentinel is a joint endeavour between Europe and the US, and will continue the measurements that have been made by a succession of spacecraft, called the Jason-Topex/Poseidon series, going back to 1992.

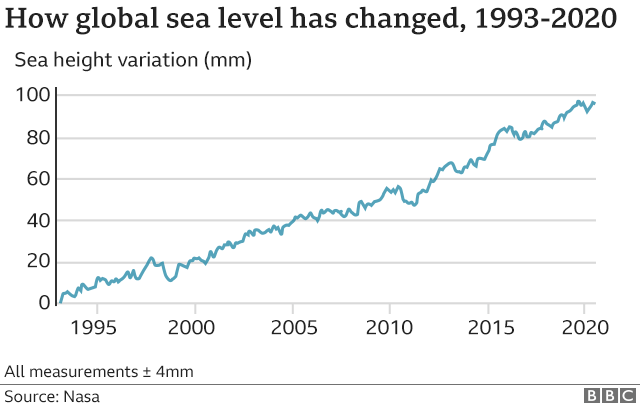

These earlier missions have shown unequivocally that sea levels globally are rising, at a rate in excess of 3mm per year over the 28-year period. And their most recent data even suggests there is an acceleration under way, with levels recorded as going up at over 4mm per year.

About half of the measured global sea-level rise on Earth is from warming waters and thermal expansion, a key driver of which is global warming. The other half is coming from melting ice.

About one-third of the measured global sea-level rise on Earth is from the expansion of warming water, a key driver of which is climate change. The rest is from melting ice.

Sentinel-6, like all the satellites before it, will use a radar altimeter to assess the height of the oceans.

This instrument sends down a microwave pulse to the surface and then counts the time it takes to receive the return signal, converting this into an elevation.

Sentinel-6 will, however, fly with a much improved capability, which will allow it to see more clearly what seas are doing right up against coastlines; and also how inland water features – rivers and lakes – are behaving.

Elevation is a key parameter for oceanographers. Just as surface air pressure reveals what the atmosphere is doing above, so ocean height will betray details about the behaviour of water down below.

The data gives clues to temperature and salinity. When combined with gravity information, it will also indicate current direction and speed.

The oceans store vast amounts of heat from the Sun; and how they move that energy around the globe and interact with the atmosphere are what drive our climate system.

But having the longest possible record of change is essential.

“The longer that time series, the better able we are to separate out the natural climate signals from the forced ones, from the human signal,” explained European Space Agency mission scientist Craig Donlon.

“It means we can run climate models backwards and then, through a validation process, have confidence that when we run them forwards we have some predictive skill.”

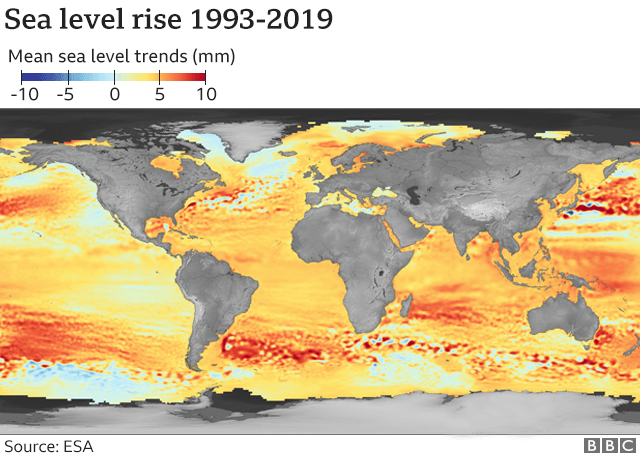

The oceans are not rising at the same rate everywhere. There are parts of the world where the elevation exceeds 1cm per year.

This is due to a multitude of factors, including changes in ocean circulation, changes in heat content, and the uneven dispersal of meltwater from ice sheets.

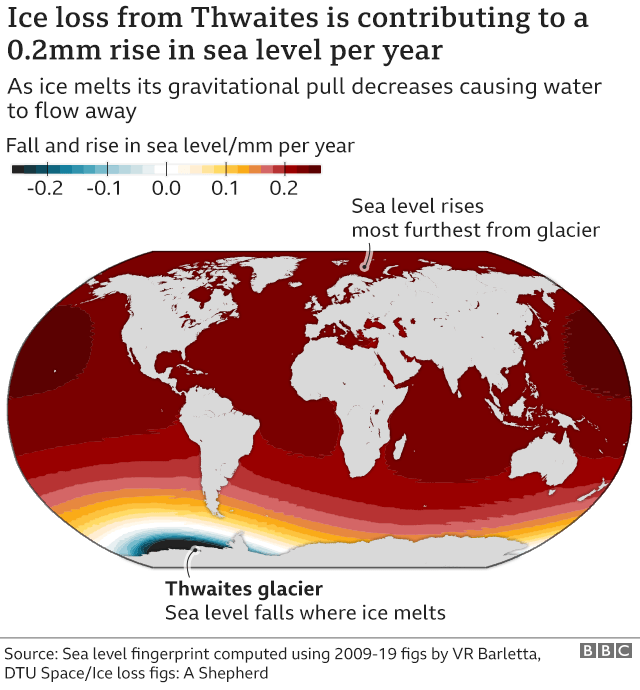

It’s a little recognised fact that the discharge from mighty glaciers, such as Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica, has the greatest effect on ocean height at far distances.

“Sea-level rise is not uniform; it’s really important to recognise this,” Christine Gommenginger, from the UK’s National Oceanography Centre in Southampton, told BBC News.

“It’s the regional sea-level budgets that we’re now targeting. Global sea-level rise – fine, we know about this. But it’s the local picture we want, and the altimetry can give us this.”

Oceanographers and climatologists, obviously. But the data is of supreme importance to the weather forecasters as well.

In the return signal is information about the state of the ocean – about how rough it is, which speaks also to the strength of the winds.

The ocean and its connection to the atmosphere is perhaps best illustrated in hurricanes. These storms get their energy from warm tropical water which an altimeter can sense by the way the sea surface bulges.

And it’s satellites like Sentinel-6 that give forewarning of an El Niño event, which sees warm waters in the western Pacific shift eastwards. This sets off a global perturbation in weather systems, redistributing rainfall and bumping up temperatures.

“Other users include ship routers – they don’t want their vessels to go through storms; they want to avoid big waves,” said Remko Scharroo, from the intergovernmental weather agency Eumetsat. “With the Sentinel-6 altimeter, we will also see the eddies in the ocean, and if you’re a ship router this information will tell you how to go with the current, not against it.”

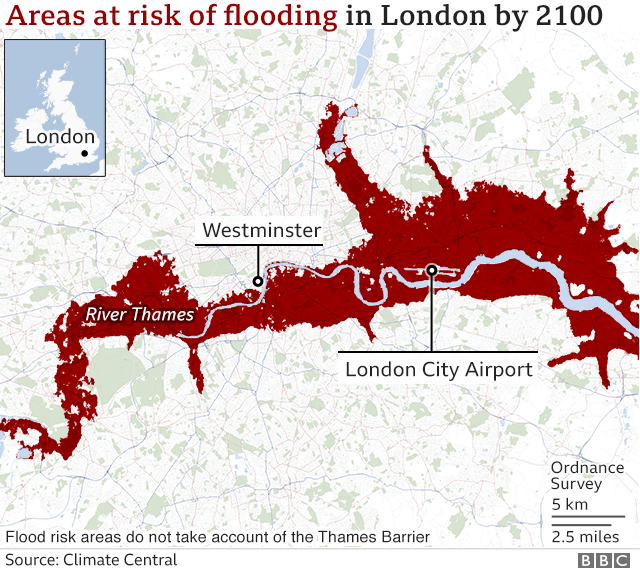

It goes without saying that coastal and flood defence planning depends on the elevation data. No new nuclear power station can be built without understanding where high tide and storm surges might reach decades into the future.

The “Sentinel” moniker is the name given to all the satellites in the European Union’s Copernicus Earth-observation programme, of which this mission is a part.

Its number shows that it is the sixth in the series of different sensor types planned for the network.

The name Michael Freilich commemorates the former director of the US space agency Nasa’s Earth sciences division who died earlier this year. He was an oceanographer by background and was instrumental in putting together the international partnership behind the mission.

“Mike Freilich exemplified the commitment to excellence, generosity of spirit and the unmatched ability to inspire trust that made so many people across the world want to work with Nasa, to advance big goals on behalf of the planet and its people,” commented Thomas Zurbuchen, who heads Nasa’s science directorate.

image copyrightESA

[email protected] and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos

Read MoreFeedzy