Now 25 years old, Amy Heckerling’s teen movie is a classic on many levels – including for how it subverts one of cinema’s most enduringly problematic tropes, writes Hanna Flint.

I

If there is one thing that Cher Horowitz, the heroine of 1990s teen-movie classic Clueless, loves, it’s a makeover. It’s her “main thrill in life,” her best friend Dionne points out, “It gives her a sense of control in a world full of chaos”. But as Cher plans the transformation of new friend Tai from grungy misfit to Beverly Hills princess, she is blissfully unaware that the person getting the real makeover in this movie is herself.

More like this:

– Why Showgirls is a horror masterpiece

– Groundhog Day meets Bridesmaids

– Why there’s no sex in Pretty Woman

Makeovers have long been a trope used by Hollywood to give films a clear narrative arc, especially in romantic comedies. The plot device of a character’s aesthetic overhaul helps to push the story forward and make a character seem more desirable, with their romantic lives often improved as a result. But 25 years ago, Clueless writer/director Amy Heckerling flipped this cliched journey on its head to deliver a witty critique of the consumerist, privileged lifestyle of Los Angeles teens.

Clueless sees Cher (Alicia Silverstone, left) making over new friend Tai (Brittany Murphy, right) – but creating a monster in the process (Credit: Alamy)

The 1995 high-school rom-com is, in itself, a ‘makeover-ed’ property. Heckerling had been asked to write a script by 20th Century Fox about youth culture; she agreed, but wanted to focus on ‘the in-crowd.’ In an interview for the original Clueless DVD release, she recalled how, as she drafted a story about what could “go wrong for a girl who always looks through rose-coloured glasses,” she realised she was writing a modern-day version of Jane Austen’s Emma.

“Unconsciously I had been writing an Emma character,” Heckerling said, “especially as she makeovers people all the time. She was very manipulative in a nice way; she lived in a fantasy of what could be for everybody else. I tried to take all the things that were in this pretty 1800s world and [imagined] what would that be like if it was Beverly Hills.”

Just as Emma Woodhouse takes the unrefined Harriet Smith under her wing, Alicia Silverstone’s queen bee begins moulding Brittany Murphy’s new kid Tai into her image. In a quick montage scene, Tai’s box dyed hair is washed out, make-up applied and her outfit overhauled (to the tune of Jill Sobule’s aptly satirical bop Supermodel) so that she can become polished enough to sit with Cher and Dionne at the top of the social hierarchy. It’s the sort of scene that appeals to audiences, says Dr Julia Wagner, lecturer in film studies at London’s Queen Mary University, because it panders to our aspirational appetites.

“The make-up, clothes and hairstyles are easy to come by, and pretty much effortless. The girl sits while other people fuss around her. Movie makeovers play out a wish fulfilment – that we can all, with just a little expertise, transform into a beautiful, confident creature.”

Tai’s confidence certainly improves as she conforms to this idealised image – but the more Cher teaches her how to dress, how to speak, and how to date, the uglier her personality becomes. Our statuesque lead has created a shallow monster and lost control of her. Thus, this vapid version of her friend holds a mirror up to our protagonist and highlights the flaws in her own superficial outlook, which is based on the assumption that everyone should fit into her world and look the part too. Soon enough, the rose-coloured glasses come off, and Cher’s perspective shifts. “I needed a complete makeover,” she says, “except this time I’d makeover my soul.”

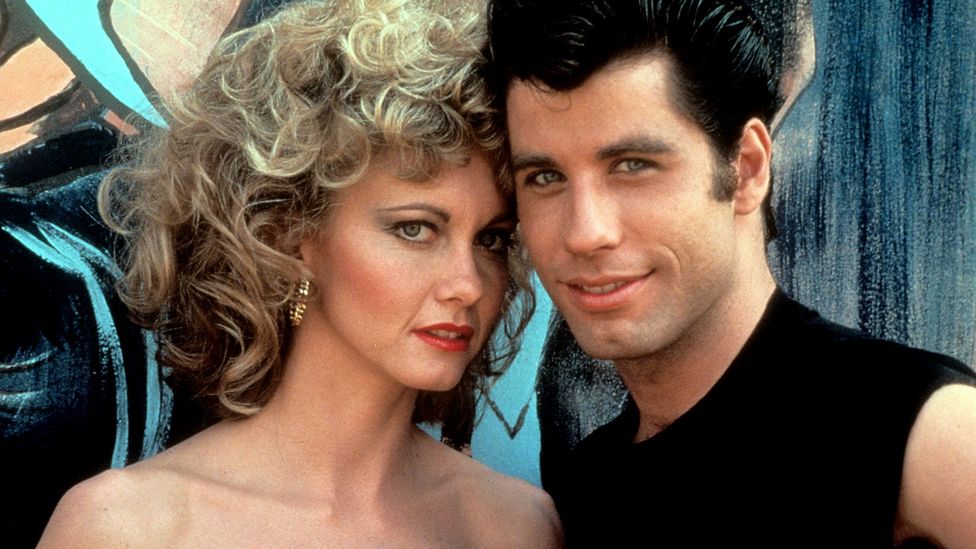

The sexed-up transformation of Sandy (Olivia Newton-John, left) in Grease is one of cinema’s most hackneyed makeovers (Credit: Elvis)

Cher begins the film already looking like an ‘after’ photo, so her transformation comes from popping the bubble of her privileged lifestyle. She participates in her teacher’s charity drive, gives away lots of her material possessions, and becomes friends with peers, like stoner Travis, who she had previously excluded. On top of that, realising that her love interest Josh is attracted to brains as much as beauty, she starts watching the news, and helping with her dad’s legal work.

Clueless is a movie that cunningly subverts the movie makeover to show how attractiveness is not only predicated on how conventionally good looking you are on the outside, but how good a person you are on the inside too. Though, it should also be noted, the film doesn’t say that wanting to look glamorous is a bad thing; come the end, Cher is still wearing designer outfits. Similarly, Legally Blonde (2001) allows its bombshell lead Elle Woods to retain her hyper-feminine style, even as she goes through an intellectual transformation while studying at Harvard Law School.

A sexist transformation

The flipside to this kind of evolution, however, is the more hackneyed one that suggests a woman is only valuable in as much as she conforms to societal beauty standards. Think of Ally Sheedy’s ‘Basketcase’ Allison being made over to look more like Molly Ringwald’s ‘Princess’ in The Breakfast Club (1985), or Sandy getting sexed up at the end of Grease (1978). That’s when the trope becomes problematic.

“I think the main problem is perhaps in the result of the makeovers, which almost always shows a standard and narrow idea of beauty,” Wagner suggests. “No one ends up with frizzier hair after a movie makeover.”

In their book The Makeover in Movies: Before and After in Hollywood Films, 1941-2002, Elizabeth A Ford and Deborah C Mitchell assert that 1941’s Now, Voyager, “established the ground rules for the makeover genre,” through the metamorphosis of Bette Davis’s depressed and dowdy spinster into a beautiful and confident heiress. “Change of appearance parallels change of fortune for heroine Charlotte Vale,” the authors write, noting that the physical traits of Charlotte’s ‘before’ appearance – no make-up, frumpy clothes, bushy eyebrows, heavy dark hair and glasses – have often been replicated in makeover movies, to varying degrees, ever since.

Pretty Woman sees Richard Gere’s millionaire orchestrate the transformation of Julia Roberts’ Vivian so that she can be elevated to his social milieu (Credt: Alamy)

Half a century later, for example, two teen films featured heroines who could have been reincarnations of Catherine in the similarities of their pre-makeover appearance. Like Catherine, too, both Mia from The Princess Diaries (2001) and Laney Boggs from She’s All That (1999) become more socially acceptable once they are beautified – She’s All That even mimics Now, Voyager’s camera shot of a pan from the shoe up show the makeover results – while also retaining some sense of autonomy by the film’s end.

An imbalance of power

However, there is an awkward power dynamic at play in both films, which is pretty typical of the makeover movie. The Princess Diaries sees a queen force her civilian-raised granddaughter to change her looks and behaviours in order to fit in with the elite circles of her birthright. She’s All That takes its cues from My Fair Lady by seeing a rich popular jock transform a less wealthy art nerd into a prom queen for a bet. “At the heart of many movie makeovers, the powerless are physically manipulated by the powerful characters,” Wagner explains. “The ostensible aim is the made-over person’s sexual and social empowerment, but it is of benefit to the (initially) more powerful characters.”

It’s even more problematic when a man is in charge of a woman’s makeover. In Miss Congeniality (2000), domineering pageant coach Victor Melling and FBI agent Eric Matthews are in charge of Gracie Hart’s transformation from ungroomed cop to beauty queen, while in Up Close and Personal (1996), news director Warren Justice (Robert Redford) controls and refines the career of younger reporter Tally (Michelle Pfeiffer) for network TV, and becomes more attracted to her as she changes. Pretty Woman (1990) sees Richard Gere’s millionaire Edward buy Julia Roberts’s sex worker Vivian for a week to play the role of his girlfriend. He orchestrates her style and etiquette transformation so that she can be elevated to his social milieu and fit in with his life, sacrificing her own in the process.

As in Pretty Woman, class mobility has also long been a key aspect of the makeover trope, ever since Cinderella had to dress the part of a princess in order to land Prince Charming. However not every female protagonist’s transformation means turning their back on their former life. In The Hunger Games (2012), Katniss Everdeen retains her working-class, District 12 identity despite the makeover she is forced to have upon arrival in the elite Capitol. Maid in Manhattan (2002) and Working Girl (1988) see two women from working-class backgrounds find their happily ever after with wealthier men after a makeover, but they are both still working by the movie’s end. Crucially, they are also in charge of their own beauty transformations – something that Wagner believes makes them far more feminist.

“I’d like to see more films where a woman chooses to have a makeover, rather than have it done to her,” she says. “Not for her wedding or a date with a man who’s deemed out of the plain girl’s league.”

Is a makeover ever truly empowering?

Last year’s comedy-drama Brittany Runs a Marathon fits this bill as it sees the titular Millennial choosing to transform her lifestyle not for a love interest, but after learning that her health is at risk. Brittany goes from a slobby, overweight slacker who can barely run around her block to a slimmed-down (though not size zero) seasoned runner, whose commitment to her fitness has led to improvements in nearly every aspect of her life. “I love putting out the message of body positivity and I think it’s time we celebrate the way we look,” star Jillian Bell said to me, championing the film’s importance, when I spoke to her for its release. “How many years have we been told that this one size and this one look is the right size and look? I’m just tired of it.”

Last year’s ‘fitspo’ comedy-drama Brittany Runs a Marathon was both praised for body positivity and criticised for perpetuating fat-shaming (Credit: Alamy)

But even a seemingly self-empowered makeover like this can be questionable: some criticised Brittany Runs a Marathon’s ‘fitspo’ narrative for still perpetuating fat-shaming, while erasing the experience of plus-size runners. “The story we’re too often told about fatness and running is that body size is an obstacle to overcome in our quest for glory,” writes Kate Brown in an article about the film for Runner’s World. “You may start out fat, slow, sweaty, and out of breath, but stick with it long enough and you’ll become a svelte, glowing running machine.”

It’s the teen-movie genre that continues to provide the smartest makeover takes, with recent films like Booksmart and Dumplin’ following Clueless in subverting the trope, and rejecting its most cliched aspects. In the former, the lead duo’s dress-up montage ends with them looking the same but in matching blue jumpsuits, while the latter sees a diverse range of girls and non-binary contestants enter a beauty pageant without needing to conform to antiquated beauty standards in order to compete. In fact, the only transformation that plus-sized protagonist Willowdean goes through is similar to Cher Horowitz: a makeover of the soul that sees her gain confidence and reconnect with her mother.

But while the cinematic makeover has gone through plenty of iterations over the years, in line with the broadening range of women’s stories on screen, what about men? The superhero genre is certainly full of makeovers: Steve Rogers’ transformation in Captain America: The First Avenger (2011) is an iconic moment. And in the past, male-led rom-coms like Can’t Buy Me Love (1987), Crazy, Stupid Love (2011) and Hitch (2005), have used the plot device – though the latter two films see makeovers orchestrated by men who also teach their male students to use misogynistic ways to manipulate women into either sleeping or falling in love with them.

However, in general, male makeovers have not featured anywhere near as prominently in popular culture as female ones. Wagner hopes that will change. “I’d like to see more men undergo makeovers in films – and not just Clark Kent taking off his glasses.” She points to the success of Queer Eye, Netflix’s hit reboot of Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, as an example of how the male makeover can make for rewarding material. “[The show’s] success proves that men can gain a lot from a makeover, so the man’s makeover should also make its way into the movies.”

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.