In our latest essay in which a critic reflects on culture that brings them joy, Jack King explains why, for all their cheesy reputation, the YMCA hitmakers fire him up like few others.

I

I can’t recall exactly where I was when I first heard a song by the Village People. I was doubtless very young – as I remember, the venue was either a school disco or a wedding reception. It certainly wasn’t a sordid affair. I should admit immediately, though, that I suspect this memory to be made up. This is probably where we all imagine we heard Village People for the first time – those of my generation, at least: such is the way their biggest hits have become the sonic staples of our biggest events and get-togethers.

More like this

– Pop music’s greatest philosopher

– The perfect crime drama to watch now

– Films that make the countryside seem less white

However, be this memory real or simulacrum, it strikes me as hilarious given what the Village People are universally known for: tongue-in-cheek gay innuendo, sparsely covered by a flimsy veneer of hyper-macho drag. But they’re not ‘just’ gay. They’re almost overtly (homo)sexual. Their signature song YMCA – one of the most famous of all time, most recently appropriated by Donald Trump supporters, who have turned it into M-A-G-A – is about cruising for sex in a mens’ health club; others celebrate traditionally male-oriented institutions such as the navy and the police.

Despite being queer pioneers, the Village People are now more often thought of as novelty act, thanks to hits like YMCA and Macho Man (Credit: Gett Images)

Yet, because of the band’s supremely cheesy reputation, their music passed me by for a long time. I avoided it quite organically, actually; we all have to at least pretend we have high tastes, after all. Can you imagine being caught listening to the Village People with any kind of sincerity?

Then, around a year and a half ago, I listened to their music out of choice – the listen that changed it all. It was actually an accident of Spotify’s algorithm – I had been listening to an album by revered disco pioneer Patrick Cowley, whose ethereal, frisky compositions, often soundtracks to ’80s porn films, couldn’t be more different from the Village People’s stereotypical garishness. However the service’s automatic run-on feature clearly disagreed and decided that, when Cowley’s sensual, gay bathhouse-ready rhythms ended, ‘Macho Man’ would be a great follow-up. And so the opening drums of the track began: a repetitive “tssh-tssh-tssh, tssh-tssh-tssh”, a simple beat, but one which demands you shake your ass.

The chorus of Macho Man has washed through pop culture like torrential rain. We’ve all heard some variation on the theme, be it the original, a football stadium chant, or Homer Simpson’s ‘Nacho Man’. Yet unlike most flash-in-the-pan pop hits, which stick to the teeth of pop culture like toffee, this was genuinely catchy. I let the song play out a few times. Once the novelty had worn off somewhat, I flicked on to another song, one I’d not heard (of) before: San Francisco (You’ve Got Me), a punchy, queer-coded ode to the bayside Californian city, which reimagines it as a hedonistic utopia (“Freedom is in the air, yeah / searching for what we all treasure: pleasure”).

For better or worse, I was hooked — and soon I’d listened to nearly their entire discography. I found their later albums pretty awful, but I heavily rotated the first three (Village People, Macho Man, and Cruisin’) for a good six months, plus one or two other singles. It was all so fun; some songs, like Milkshake, which is literally about making a milkshake, were hilariously bad and more joyous for it. San Francisco, with its celebratory high tempo and soul-grasping jubilance, became my on-repeat running anthem. And I was fascinated by the empowerment I felt from Village People, the title track on their eponymous debut album, and an unambiguous call for gay liberation that sounds more akin to a protest chant than a chart topper. It lit a fire in my gut in a way few queer artworks have before. And all this from the Village People?

The politics of disco

Well, yes. Said first three albums (and especially the first two) carry a surprisingly political energy; the more popular tracks, such as the eponymous Macho Man, might be vacuous but others – take I Am What I Am, a defiant chant that suggests exactly what you’d expect it to suggest – envision a world in which male bodies could be free to come together without oppression.

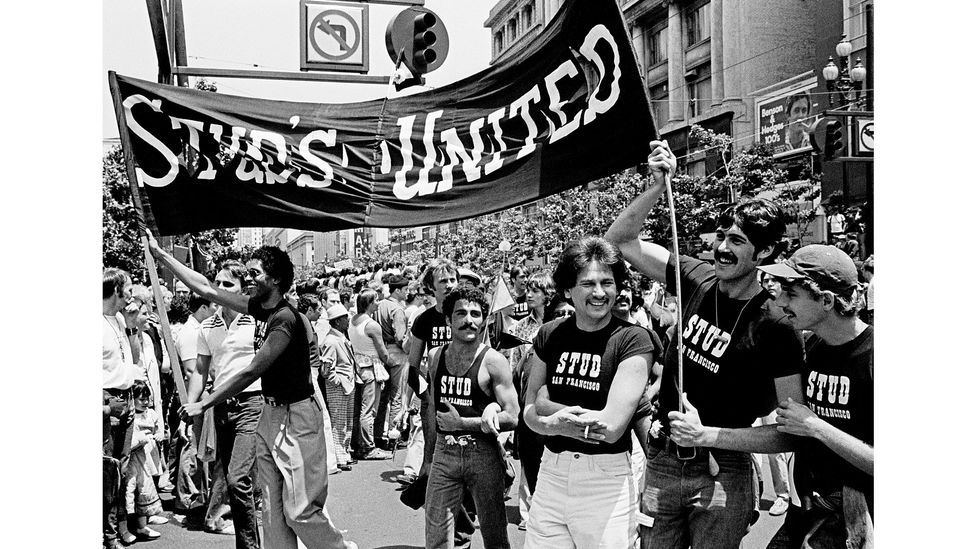

San Francisco was one of the gay meccas the Village People celebrated on their visionary debut album (Credit: Alamy)

As far as evoking same-sex love goes, there was a precedent – from disco’s genesis, queered sexual positivity was the life blood of the genre, as Peter Shapiro identifies in Turn the Beat Around: The Secret History of Disco. “As the cultural adjunct of the gay pride movement, disco was the embodiment of the pleasure-is-politics ethos of a new generation of gay culture, a generation fed up with police raids, draconian laws and the darkness of the closet,” he writes. “That this new movement was born on the night of Judy Garland’s funeral couldn’t have been more appropriate.”

That said, the genre’s lyrics tended to eschew more overt political statements – and the few that did carry an unambiguous message of gay liberation didn’t chart well. Queer pop historian Martin Aston cites the example of Carl Bean’s I Was Born This Way, released three decades before Lady Gaga’s riff on the same theme: “I Was Born This Way sold respectably but never charted. […] Political disco was almost an oxymoron.” Yet, despite this, the Village People’s eponymous debut, certainly, can hardly be described as apolitical, even if it is the group’s reputation for frivolity that has endured within popular consciousness.

In her disco chronicle Hot Stuff: Disco and the Remaking of American Culture, Alice Echols recalls a 1978 Rolling Stone article in which Jacques Morali – the French producer who, alongside Henri Bolelo and eventual group leader Victor Willis, created the Village People – put forward a manifesto of gay visibility: “Morali outed himself, and emphasised that as a homosexual he was committed to ending the cultural invisibility of gay men. ‘I think to myself that gay people have no group,’ he said, ‘nobody to personalise the gay people, you know?'”

Indeed, the themes of their first LP serve to support this intent. The album is comprised of paeans to the United States’ gay underbelly, focusing on four places: San Francisco, Hollywood, Fire Island and Greenwich Village. The combination of locales alone should immediately tip you off as to who Village People was being sold to, as any gay man in the late 70s would recognise this as a laundry list of US gay meccas.

Not only an ode to the city, San Francisco (You’ve Got Me) celebrates freedom of the self. It knowingly evokes the sex-as-politics attitude of gay liberation (“Love the way I please / don’t put no chains on me”), and Victor Willis’ cry of “leather, leather, leather baby” speaks to the era’s emergent gay macho archetype. Out was victimisation, in their eyes, and in were muscles and moustaches. The song also evokes the great gay urban migration of the 1970s, during which gays and lesbians across the US moved to urban centres – San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York City – en masse. This theme is seamlessly carried over to In Hollywood (Everybody is a Star), which envisions Hollywood as a cartoonish hub of opulence, universal success and stardom – an aspirational portrait for a historically marginalised class.

As their career went on, the Village People increasingly courted the mainstream, including with 1980 film Can’t Stop the Music (Credit: Alamy)

For something unabashedly homosexual you need only turn to Fire Island, named after the most iconic gay hotspot in the world, a thin strip of land some 50 miles off the coast of New York City, revered for its hookup spots and orgiastic dances. Directly referencing such famous bars and clubs as The Ice Palace and The Sandpiper (which, by the way, is where they’re “peckin'”), Fire Island evokes unashamed queer sexual desire: “You never know just who you’ll meet / Maybe someone out of your wildest fantasies.”

And then we come to the titular track Village People, the most emphatically political of them all; a percussive chant that calls upon the ‘Village people’, thin code for gay men, to “take our place in the Sun”: “To be free,” Village People declare, “We must be / all for one.” It’s a revolutionary statement through-and-through. The song envisions a new age of sexual freedom, advocating for unity against the homophobia that was de rigueur in US society in the late 70s.

A part of queer history

I’m not arguing that the Village People are peerless artists, and even if I did think that, I probably wouldn’t admit it. The band’s motives, for one, have to be questioned. Empowering and queer-focused as their early lyrics may have been, the message quickly shifted once mainstream success was courted and deemed to be more profitable than their initial target group of gay disco-goers. It would seem they followed the money. And so it would be hagiographic to enshrine them as gay political pioneers, Jacques Morali’s manifesto for gay cultural visibility or otherwise.

But for a gay man, it is impossible, too, not to have a visceral response to Village People and its – somewhat superficial but incredibly energising – call for gay liberation, in such unambiguous terms. Even in the last 40 years, how many songs have so emphatically called for queer unity, and for hope? Certainly, if the tune makes me ecstatic, I can’t begin to think of what it would be like for a guy in 1979, newly discovering his gayness and hearing it for the first time in a pulsating New York nightclub.

It’s in this sense that Village People can serve as a bridge to the past, for me and many other young queer people. I’m fascinated by historical queer culture, forged as it is by community revolts and political struggle, and the joy I derive from their music comes in part from the lineage their music evokes. The imagined history that pops into my head when I hear such songs as Fire Island – of free men dancing in pulsating clubs, their shirtless bodies entwined.

I’m certain some might find my love for the Village People ridiculous, and it’s hard to entirely disagree. But at the end of the day, as the song goes: “I didn’t choose the way I am.” You might even say I was born this way.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.