What is revealed by the early manuscripts of classic novels? From the works of Wilde and Woolf to Fitzgerald and Proust, Hephzibah Anderson investigates.

W

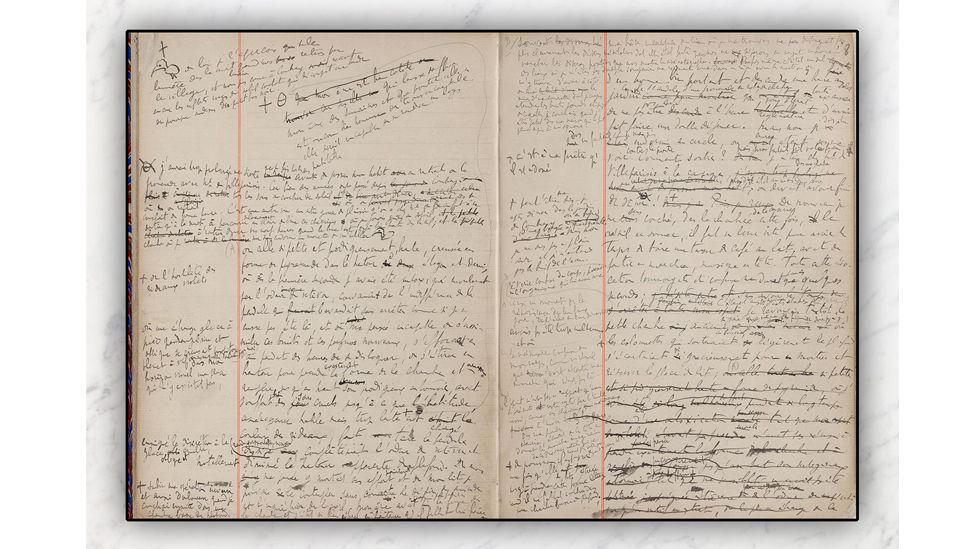

Writers who find themselves mired in procrastination would do well to take a page from Marcel Proust’s most famous book. Specifically, a page from In Search of Lost Time in manuscript form. Nothing more powerfully illustrates the truth of that creative-writing-class maxim, ‘writing is rewriting’, than the liberally crossed-out, lavishly annotated, occasionally doodled-upon notebooks in which Proust composed his seminal, seven-volume text.

More like this:

– The greatest summer novels ever written

– The cult books that lost their cool

– The best novels you’ve never heard of

While their faded ink and age-dappled paper evoke physical fragility, what they showcase is a robust, almost aggressive determination. This is the heavy lifting of literary endeavour made manifest; there is no preciousness here, nothing is sacred. However much Proust doubted himself – and he doubted his chosen art form, too – he pressed on with a monumental task that would occupy him for the rest of his life. As for that iconic morsel of memory-laden cake, the madeleine, it started out as a slice of toast and a cup of tea.

The notebooks in which Proust hand-wrote his masterpiece In Search of Lost Time are full of the author’s revealing notes (Credit: SP Books)

The manuscripts of literary works-in-progress fascinate on many levels, from the flush-faced thrill of spying on something intensely private and the visceral delight of knowing that a legendary author’s hand rested on the paper before you, to the light that such early drafts shed on authorial methodology and intent. Sometimes, the very essence of what a writer is trying to express seems to hover tantalisingly in the gap between a word deleted and another added in its place.

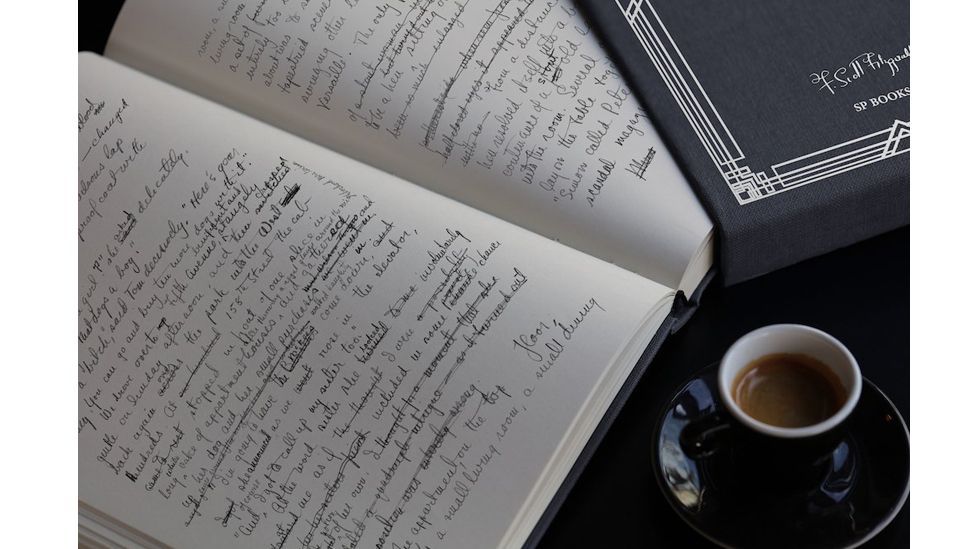

Elsewhere, discombobulating differences can inspire in the reader fresh takes on even the most well-thumbed texts. Openings and endings turn out to have been quite different in their earliest renderings, and beloved characters are to be found taking their first steps bearing very different names. For instance, Gone with the Wind’s Scarlett O’Hara was originally called Pansy, Arthur Conan Doyle’s deerstalker-wearing detective answered to Sherrinford Hope, and The Great Gatsby’s Daisy and Nick were Ada and Dud.

The original manuscript of The Great Gatsby reveals intriguing details about Fitzgerald’s intent and method (Credit: SP Books)

Seemingly small changes can make an enormous difference but as novelists write their way into stories, they sometimes find themselves radically rethinking plots. When Virginia Woolf first conceived Mrs Dalloway, it was a novel in which the eponymous heroine, a character who’d already appeared in her debut, The Voyage Out, would kill herself. Instead, it’s Septimus Smith, a shell-shocked World War One veteran, who will jump to his death. In the notebooks in which she drafted the novel, she can be seen developing him in a way that seals his fate. Meanwhile, the novel’s title vacillates between the one we know and another, later borrowed by novelist Michael Cunningham for his own novel based on Woolf’s life and works: The Hours.

In a detail sure to set every graphophile’s pulse racing, Woolf wrote in purple ink. She ruled her own margins in blue pencil and used them not just for insertions but also to tot up her word count, a very practical way of cheering herself on. There are diary-like confidences, too: “a delicious idea comes to me that I will write anything I want to write”, she declares at the top of one page, in bracing contrast to the self-doubts that were simultaneously besetting her. As she told her diary on the day she reached the 100th page of her draft: “It may be too stiff, too glittering and tinselly”. Still, she continues writing and revising until, less than a year later, in 1924, she’s changed her view. “There I am now – at last at the party… Now I do think this might be the best of my endings.” The novel was published in 1925.

Magic and meaning

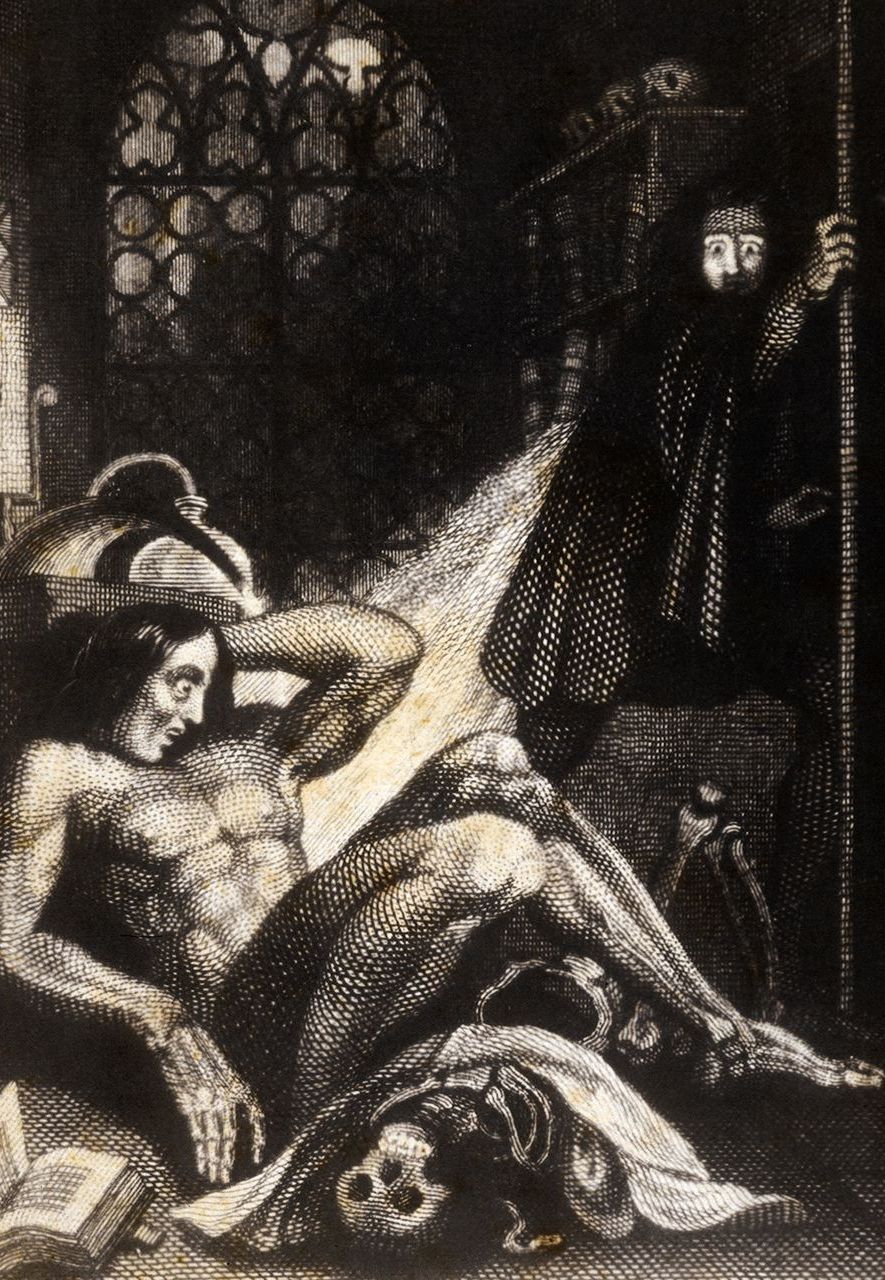

When Frankenstein first appeared in print in 1818, anonymously but with a preface by Percy Bysshe Shelley, plenty of readers assumed that the poet was its author. In Mary Shelley’s introduction to the 1831 edition, she wrote that people had asked her “how a young girl, came to think of, and to dilate upon, so very hideous an idea?” In keeping with the story’s eerie origins – the stormy nights and sunless summer days beside Lake Geneva – she put it down to a kind of visitation, the result of “imagination, unbidden, possessed”. Yet as the manuscript reveals, inky-fingered graft played a big role in allowing the doctor’s monster to evolve into the more tragic, nuanced creature that’s haunted our imaginations ever since. In fact, “creature”, Mary’s initial description, is later replaced by “being”, a being who becomes still more uncannily human thanks to other tweaks such as replacing the “fangs” that Victor imagines in his feverish delirium with “fingers” grasping at his neck.

The first draft of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein shows how the figure of the ‘creature’ evolved in the author’s imagination (Credit: Getty Images)

Sadly, the refusal to believe that a woman barely out of girlhood could possibly have authored this transcendent Promethean fable has never quite gone away, and Percy’s notes on the manuscript have been used to bolster the theory that he at least co-authored Mary’s novel. While he’s certainly an astute line editor, the chief revelation here is domestic: the radical Romantic was a supportive, affectionate partner. Correcting her spelling of “enigmatic” (in keeping with her propensity for doubling up the letter “m”, the home-schooled teen wrote “igmmatic” – Percy’s own misspellings tended to muddle the “i before e” rule), he adds a fond and flirty “O you pretty pecksie!”. He, meanwhile, is her “Elf”.

In The Art of Fiction, Dorothy Parker says “I would write a book, or a short story, at least three times – once to understand it, the second time to improve the prose, and a third to compel it to say what it still must say.” But the world isn’t receptive to all messages, as Oscar Wilde knew. The Picture of Dorian Gray, his best-known work, began life as a short story, and as the manuscript shows, his changes incorporated a degree of self-censoring. References to Basil Hallward’s relationship with Dorian are toned down. Basil talks of Dorian’s “good looks” instead of his “beauty”, while his “passion” becomes “feeling”.

Other passages are crossed out entirely, among them Basil’s confession that “the world becomes young to me when I hold [Dorian’s] hand.” Wilde’s editor, James Stoddart, censored it further but its publication in the July 1890 issue of Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine still caused uproar. Critics slammed it for being everything from plain “nasty” to “heavy with mephitic odours of moral spiritual putrefaction”, and the bookseller WH Smith refused to stock the magazine.

An early manuscript of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray reveals the author’s self-censorship (Credit: Alamy)

Wilde’s notebook drafts, along with those of Shelley, Woolf and Proust, all feature on the backlist of an innovative small press seeking to preserve the visual, tactile encounter provided by early drafts. Founded in Paris in 2012, SP Books publishes limited facsimile editions of literary manuscripts. Large format and assembled by hand, each book is beautiful, from its gilded slipcase to its heavy paper. As SP co-founder Jessica Nelson tells BBC Culture: “In the context of an increasingly digitised world, our goal is to restore the magic of writing as a potent vehicle between the artist and his or her work. We feel strongly about the importance for today’s reader to be able to connect with the author’s hand and delve directly into the manuscript”. It comes at a price, of course: these collectibles are not cheap.

The original notebooks and manuscripts are mostly locked away in libraries and academic archives, where access is by necessity strictly regulated. It hasn’t always been this way, though. A couple of centuries ago, such veneration would have seemed bizarre. There’s a danger to fetishising these relics and their analogue authenticity: literature’s real vitality, let’s not forget, lies in its ability to fly off the page, and books ultimately belong to their readers. Even so, it’s hard to resist the dynamism of pages from a manuscript like Vladimir Nabakov’s first draft of Invitation to a Beheading, complete with curling arrows and asterisks. This, surely, is as close to being inside an author’s head as it’s possible to get. Pages from early drafts of Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead convey a similarly vivid impression.

Virginia Woolf radically re-thought the plot of Mrs Dalloway while writing the book (Credit: Alamy)

Robinson, along with the likes of Paul Auster and Martin Amis, is one of a dwindling number of authors who still draft in longhand. The poet Philip Larkin told the Paris Review that the literary manuscript holds ‘magical’ and ‘meaningful’ value, and penmanship seems vital to the former. Whether it’s Kafka’s herky-jerky script, pulsing with eccentric energy, or George Eliot’s, which seems to exude a confidence she rarely felt off the page, handwriting conveys something of an author’s state of mind in a way that ‘track changes’ simply can’t.

Then again, it also presents its own challenges. Sometimes, a manuscript’s chief contribution to literary scholarship lies in straightening out typographic errors previously introduced by an author’s hasty scrawl. In one noted episode, laurelled Harvard scholar F O Matthiessen hung a discussion about discordant harmony in the work of Herman Melville on the phrase “soiled fish of the sea”, which crops up in White Jacket, Melville’s fifth book. As it turned out, the adjective was “coiled”, and the author was merely describing eels.

Love books? Join BBC Culture Book Club on Facebook, a community for literature fanatics all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.