The story of queer country music – and its message of hope

As LGBTQ+ country artists like Orville Peck and Lil Nas X blaze a trail, Addison Nugent looks at the surprising and little-known tradition of queer country music that preceded them.

I

In 2019, a mysterious masked crusader by the name of Orville Peck took the alternative country scene by storm with his debut album Pony. Known for his soaring vocals (a mix of Glen Campbell and Roy Orbison), fringed leather mask and haunting, erotic lyrics, Peck felt like a much-needed breath of fresh air in a genre that seemed to have stagnated since the 1970s. He, along with Lil Nas X – whose hit Old Town Road became the longest-running number-one song ever – and Trixie Mattel of RuPaul’s Drag Race fame, are at the forefront of a new wave of country music that includes the LGBTQ+ community. And although they may be considered mavericks and outliers in the largely conservative world of country music, the genre actually has a long-standing, though little-known, queer history.

More like this:

– Is Lady Gaga a genius or a copycat?

– All hail the cleverest men in pop

– The Picassos of modern music

Queer country and queer country musicians have arguably existed since the very beginning of the genre in the late 1920s and early 1930s. After all, queerness has been present in all aspects of society throughout human history. The very first gay country song is thought to be I Love My Fruit by The Sweet Violet Boys. More widely known by their other name, The Prairie Ramblers, the group decided to take on a pseudonym to record some scandalous songs written by their pianist Bob Miller.

Orville Peck’s debut album Pony took the alternative country scene by storm (Credit: Getty Images)

And I Love My Fruit, full of sexual innuendo, certainly was scandalous for the year 1939. Little is known about The Sweet Violet Boys or their true sexualities but it would be strange for a group of straight men in the 1930s to risk their careers if not their lives in order to masquerade as queer cowboys.

Another early queer country musician was Wilma Burgess, who had several smash hits in the 1960s including Misty Blue and Baby. Today, Burgess is often touted as the world’s first ‘out’ country singer within the music industry, although not publically. Still, Burgess wanted to avoid ‘playing straight’, and insisted that the majority of her songs remain gender neutral or ambiguous. By 1978, she had grown frustrated with the piousness of the country music scene, and left the business. A decade later, using the money she’d made in her music career, she opened Nashville’s first lesbian bar, The Hitching Post.

Wilma Burgess had several hits in the 1960s, and avoided ‘playing straight’ (Credit: Getty Images)

The first true queer country album was Lavender Country’s self-titled release in 1973. At the band’s helm was (and still is) singer, songwriter, and guitarist Patrick Haggerty, a lifelong gay-rights and anti-racism activist, sometime politician, and self-described “screaming Marxist bitch”. In 1970, just one year after the Stonewall riots, Haggerty moved to Seattle, Washington, where he became involved with the Gay Community Social Services of Seattle, one of America’s first such organisations for the queer community. Haggerty formed Lavender Country in 1972, and the band played regularly at gay pride events up and down the West Coast. The album features songs about injustice in all aspects of society but most notably in the gay community.

With songs like Crying these Cocksucking Tears and Come Out Singing, Lavender Country wasn’t just the first queer country album but one of the first out-and-proud albums of all time. Unlike many members of the LGBTQ+ community of his generation, Haggerty did not have to struggle to find pride later in life. His father, born on the North Dakota prairie in 1901, accepted and embraced Haggerty’s self-described “sissiness” his entire life. “My father loved me so I loved myself. My father was proud of me so I was proud of myself,” he tells BBC Culture.

Patrick Haggerty of Lavender Country has stood against injustice throughout his career (Credit: Getty Images)

His father’s acceptance carried him through his school years in the 1950s in the small town of Dry Creek, Washington, where in spite of the socially conservative time, Haggerty was wildly popular. His dad would even drive him to school dressed in full drag as the school’s glitter-covered mascot Peppy Pat, a character Haggerty created himself. As high school approached, his parents and 10 siblings began to worry that as the town’s only ‘sissy’, Haggerty might face more bullying than he had in previous years. His father gave him this advice: “You’ll be alright, just remember this: you’re no better than any of the rest of them but you’re just as Goddamn good, and if anybody gives you any grief about that, hit ’em with your purse.”

After enjoying a few years of underground success, Lavender Country disbanded in 1976, entering a 40-year fallow period during which time Haggerty married his partner of 31 years and began performing for sufferers of Alzheimer’s at care homes.

Rednecks, queers and country music

At the same time as Lavender Country’s pioneering contribution to country music, however, the genre as a whole became strongly associated with intolerance, making the notion of queer country seem antithetical. The stereotype of the flannel shirt-sporting, bearded, long hair topped with a trucker cap, country-music loving ‘hick’ has now become emblematic of backward, and homophobic, thinking – as seen for example, in Taylor Swift’s You Need to Calm Down music video in which white working-class people are shown protesting against gay rights. This, according to Dr Nadine Hubbs, author of Rednecks, Queers, and Country Music, is born of deep-seated classism.

“Up until the mid-20th Century, the ‘sin’ of the working class had been that they were a bunch of immoral, deviant, queer lovers,” Dr Hubbs tells BBC Culture. “Then in the ’70s when social politics took such a big turn with the women’s rights movement, the gay rights movement, the civil rights movement, it wasn’t cool for middle-class people to be intolerant. It was cool to be tolerant, so somehow the sin of the working-class became that they were a bunch of degenerate, deviant, queer haters.” As a result, the working-class queer community, one that, in Dr Hubbs’ words, has existed “as long as we can possibly document”, was essentially erased from the genre.

Karen Pittelman of Karen and the Sorrows is a passionate advocate for lesbians in country music (Credit: Amanda Kirkhuff/ karenandthesorrows.com)

This began to change for a brief period in the early 1990s with artists like kd lang but queer country didn’t really take off again until the 2010s thanks to Karen Pittelman of Karen and the Sorrows. In 2011, Karen began hosting The Queer Country Quarterly in Brooklyn, an event showcasing queer country artists that quickly spread across the country. A lifelong country fan and musician, Pittelman felt the need to create a space where she, as a lesbian, and others within the queer-country community would feel safe and welcome. “I really missed playing in queer spaces, and that felt like home to me,” she says. “I didn’t want it to be weird that I was in love with my pedal-steel player and I just wanted to get to play shows where I felt I was with my community.”

One of the mainstays of the Queer Country Quarterly is Paisley Fields, whose first album Not Gonne Be Friends debuted to critical acclaim in 2014, and latest album is this year’s Ride Me Cowboy. Paisley, who grew up in the Midwest where he was a church pianist as a teenager, remembers country music, and specifically line dancing, as a means of expressing (if covertly) his sexuality in a conservative setting. “When I was line dancing I could just dance around and be a little gay boy and no one would judge me for it,” he recalls. Along with touring with his own band, Paisley is also a member of the reactivated Lavender Country.

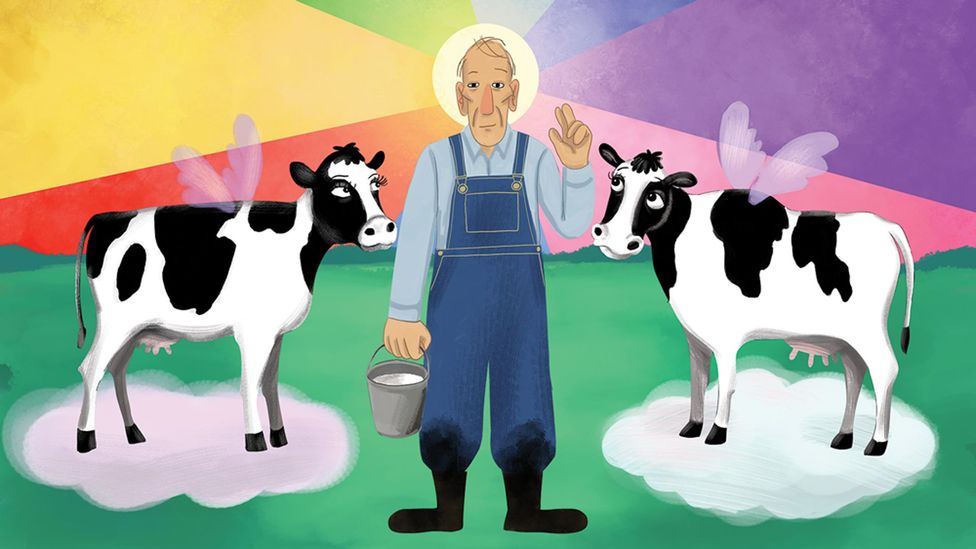

The animation The Saint of Dry Creek tells the story of Patrick Haggerty’s childhood (Credit: StoryCorps)

Haggerty’s group received renewed interest when indie label Paradise of Bachelors rereleased their debut album in 2014. From there, Haggerty’s career really started to take off. The LP garnered rave reviews from Pitchfork, the Boston Globe and LA Weekly. In 2015 the story of him and his father’s relationship was made into a beautiful animation for StoryCorps called The Saint of Dry Creek. There was also a documentary: directed by New York filmmaker Dan Taberski, These C*cksucking Tears won the award for best documentary short at SXSW, as well as the jury award at the Seattle International Film Festival and the Grand Jury Prize at Outfest. Then, in 2017 Haggerty experienced what he described as “the artistic apex of a lifetime” when he sang live to a ballet created by the company Post:Ballet, to accompany Lavender Country. The Lavender Country ballet is still being performed.

Lil ‘Nas X had a huge hit recently with Old Town Road (Credit: Getty Images)

Today, Lavender Country is once again a band, with Haggerty playing shows across the country alongside a revolving roster of members. The night we speak, he is getting ready for a gig in Seattle at the DIY punk club, The Black Lodge. Does he have a message for future queer country artists? “Look, it’s too late for me to compromise now,” he says. “And I understand why people are choosing these more moderate paths in order to get to gay stardom but [in my music] it’s the raw real politic that people are attracted to. I don’t want to be a fucking star, forget it! Girlfriend, it’s all about the message.”

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.