image copyrightJeronimo Zuñiga/Amazon Frontlines

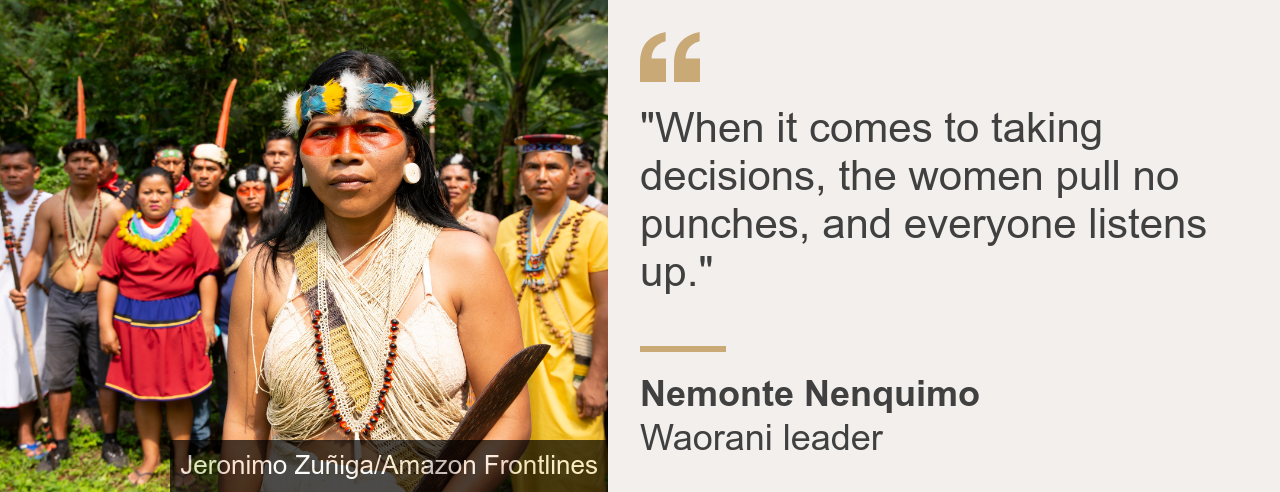

An indigenous leader from the Ecuadorean Amazon is one of the winners of the Goldman environmental prize, which recognises grassroots activism.

Nemonte Nenquimo was chosen for her success in protecting 500,000 acres of rainforest from oil extraction.

She and fellow members of the Waorani indigenous group took the Ecuadorean government to court over its plans to put their territory up for sale.

Their 2019 legal victory set a legal precedent for indigenous rights.

For Nemonte Nenquimo, protecting the environment was less a choice than a legacy she decided she had to carry on.

“The Waorani people have always been protectors, they have defended their territory and their culture for thousands of years,” she tells the BBC.

image copyrightGetty Images

- Number around 5,000 people

- Traditional hunter-gatherers organised in small clan settlements

- Among the most recently contacted peoples: reached in 1958 by US missionaries

- Waorani territory overlaps with Yasuni National Park, one of the world’s most biodiverse ecosystems

- 80% of the Waorani now live in an area one-tenth the size of their ancestral lands

Ms Nenquimo says that when she was a child she loved to listen to the elders tell stories of how the Waorani lived before they were contacted by missionaries in the 1950s.

“My grandfather was a leader and he protected our land from incursions from outsiders, he literally spearheaded that defence by confronting intruders, spear in hand.”

Ms Nenquimo says that from the age of five, she was encouraged by the elders to become a leader herself.

“Historically, the Waorani women have been the ones to make the decisions, the men went to war,” she explains.

“Waorani women made the men listen to them and it wasn’t until we had contact with the evangelical missionaries that we were told that God created Adam and that Eve came second and was created from Adam’s rib, that’s when the confusion [about women’s role] started.”

But Ms Nenquimo insists that the role of women in Waorani society continues to be a key one. “When it comes to taking decisions, the women pull no punches, and everyone listens up”.

Nemonte Nenquimo says that she may be the first woman to have been chosen as president of the Waorani of Pastaza province but “there are many women leaders” among the Waorani, who she says have been guiding her in her fight to protect their territory from oil extraction.

While Ms Nenquimo grew up in an area of rainforest where there was no drilling for oil, she recalls the first time her father took her to visit her aunts, who lived near an oil well.

“We went first by canoe, and then walked for 19 hours and even though we were still far from the well, I could hear the noise,” she recalls. “I was 12, and the impact it made was very strong, to see the flames and smoke shooting from the oil well.”

But it was not just the environmental impact that shocked her, but also the negative effect life in the settlement by the well had on Waorani families.

image copyrightJeronimo Zuñiga/Amazon Frontlines

“My aunt told me that life there was no good, her sons all worked in the oil industry and with the money they earned, they bought alcohol. Some became violent and would hit their wives,” she recalls.

“I don’t know how people can live there, with all that noise, it’s nothing like my home in [the indigenous community of] Nemonpare, where all you see at night is the stars and all you hear is the animals.”

image copyrightGetty Images

When almost 20 years later, in 2018, the Ecuadorean government announced that it would put 16 new oil concessions up for auction covering seven million acres of Amazon rainforest, Ms Nenquimo led the fight against the concessions.

By then in her early thirties she was not just the leader of the Waorani of Pastaza but also co-founder of the Ceibo Alliance, an indigenous-led non-profit organisation championing indigenous rights and culture.

She launched the “Our rainforest is not for sale ” digital campaign. which collected almost 400,000 signatures from around the world opposing the auction.

She also acted as a plaintiff in a lawsuit against the Ecuadorean government arguing that it had not obtained prior consent from the Waorani to put the land – much of which overlaps with Waorani territory – up for auction.

In April 2019, the judges in the case ruled in favour of the Waorani. The ruling not only protects 500,000 acres from oil extraction but also means that the government will have to ensure free, prior and informed consent before auctioning off any other land in the future.

image copyrightGetty Images

The precedent-setting ruling was celebrated by environmental activists across the world as a rare triumph of indigenous rights over those of big business and government.

But Ms Nenquimo says she and her fellow Waorani were always confident of victory. “We were so certain that this territory is ours because we are the ones living here, we just could not permit this to happen.”

The court which ruled in the Waorani’s favour has ordered Ecuador’s legislative body – the National Assembly – to pass a bill which would enshrine prior consent in law.

But earlier this month, indigenous leaders, including Ms Nenquimo, said the bill had been drafted without any input from indigenous representatives.

“This prize will hopefully give us and our fight more visibility and create consciousness that we’re acting for the good of the planet,” she says.

Other winners of the global award this year hail from Ghana, France, Myanmar, The Bahamas and Mexico.

Reporting by News Online’s Latin America editor Vanessa Buschschlüter.

Read MoreFeedzy