The photographers changing the way we see animals

Popular culture can create stereotypes of ‘cuddly’ pandas or ‘evil’ snakes – but some photographers are setting out to change how we see wildlife, writes Graeme Green.

S

Savage and snarling, the giant gorilla of the King Kong films is a fearsome monster that needs to be appeased with a human sacrifice. Size aside, it’s a strange depiction of an animal that, as anyone who’s stood near a gorilla knows, exudes a sense of peace and gentleness. When I photographed gorillas in Uganda, I saw tumbling infants irritating their patient dad, as the family quietly chewed leaves. These are not animals that rampage violently through forests, a deadly threat to anything in their way.

More like this:

– Can photography save the Amazon?

– A secret history hiding in plain sight

– A stare that challenges us to look away

Film and literature exert a strong influence on how people think of animals, with fictional versions often far removed from reality. Sharks aren’t vengeful killers. Snakes aren’t ‘evil’. And the majority of pandas, no matter what the films say, are not masters of Kung Fu. “We’ve turned pandas into goofy, cartoonish characters,” says National Geographic photojournalist Ami Vitale, who photographed the bears over three years in China’s Sichuan province. “We’re used to seeing them as stuffed toys and in story books, but that’s not actually how they are at all. It’s a creature that’s very elusive, quiet and solitary.”

Ye Ye, a 16-year-old giant panda, in a wild enclosure at a conservation centre in Wolong Nature Reserve, China by Ami Vitale (Credit: Ami Vitale)

How animals are perceived matters, especially as the loss of wild habitat around the world is bringing people and animals into closer contact, and as other human activity, from poaching to the exotic pet trade, is driving many species towards extinction. Animals are threatened by humans, rather than being a threat to humans. Long before pangolins hit the news as a possible source of the coronavirus in Wuhan’s wildlife markets, photojournalist Brent Stirton helped bring the little-known animal to global attention as the most trafficked mammal in the world, their scales used (despite having no medicinal properties) in traditional Chinese ‘medicine’. His Pangolins in Crisis series has just won first prize in the Natural World & Wildlife category of the Sony World Photography Awards.

Brent Stirton’s Pangolins in Crisis series has just won first prize in the wildlife category of the Sony World Photo Awards (Credit: Brent Stirton)

Photography is one of the ways we can see real, complex and often incredible animal behaviour and characteristics. It’s also where we can understand the damage we’re inflicting on the natural world. Vitale’s photo of the final moments of Sudan, the last male Northern White Rhino, is one of the defining images of the past decade. “It woke people up,” explains Vitale. “You realise this isn’t just the death of this ancient, gentle, hulking creature. That moment with just one animal is symbolic of what we’re doing to this planet and every living creature on it, including humanity.”

Joseph Wachira saying goodbye to Sudan, the last male Northern White Rhino, by Ami Vitale (Credit: Ami Vitale)

Every day, we’re bombarded with images, from adverts to Instagram. But a powerful photo can still break through. “It’s wonderful to look at a beautiful image but it has to have meaning,” Vitale adds. “I want people to look at a photo, and feel empathy and understanding. Photography is the greatest communicator. It transcends country, culture, religion, background and language.”

A different reality

Nick Brandt’s often bleak photographic work is also changing how people see the natural world. His latest large-scale project, This Empty World, showed wild animals (including elephants, hyenas, and rhinos) in jarring human environments. Each image was created from two moments captured weeks apart in southern Kenya. First, a partial set was built, with cameras positioned to capture animals that entered the frame. Then, with each camera in the same position, larger sets were built and local people brought in to create scenes of bus stops, building sites, petrol stations. “Obviously it’s not real life, but it’s symbolic of what’s happening, which is ‘progress’ rapidly invading what remains of natural wildlife habitat,” says Brandt, who’s also the co-founder of the Big Life Foundation, a wildlife charity working to protect elephants and other wildlife in Kenya from threats, including human-wildlife conflict. “The biggest challenge facing the natural world in Africa today is the disappearance of wildlife habitat.”

Bus station with elephant in dust by Nick Brandt (Credit: Nick Brandt)

Though his approach is very different, Brandt also hopes his work cuts through the clutter of the modern age. “I never really know how much difference my photography makes,” he says. “You just plough on and hope you’re making a bit of difference. This Empty World paints a very dark vision. But I wouldn’t be doing it if I didn’t think there was hope.”

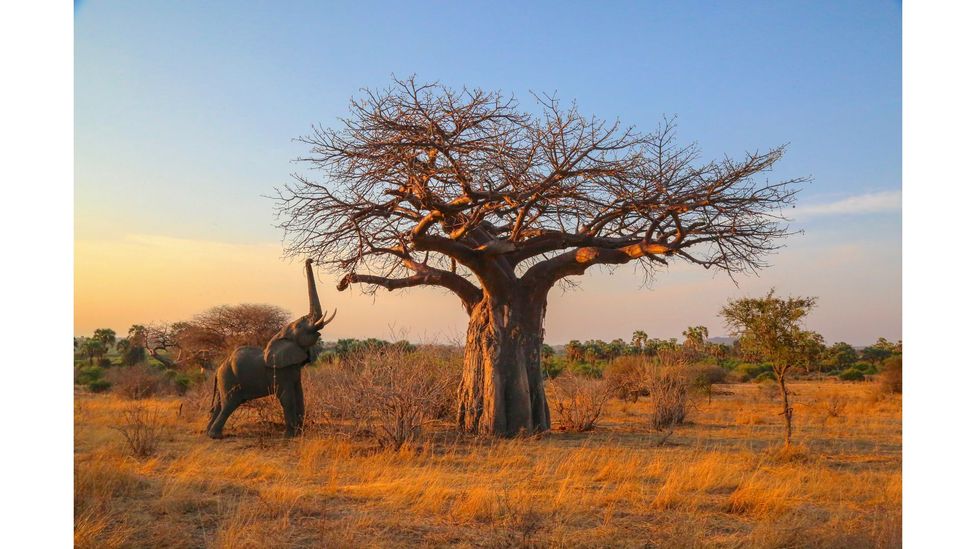

Over the last 15 years as a photographer and journalist, I’ve also seen the harm we’re causing to wildlife. The New Big Five project, which I launched recently, is asking people around the world to vote for five animals they’d like to be included in the New Big Five of wildlife photography, rather than hunting – shooting with a camera, not a gun. Again, it’s about changing how people see our relationship with wildlife. The original ‘big five’ was based on the five toughest animals in Africa for colonial trophy-hunters to shoot and kill (lion, elephant, rhino, leopard and buffalo); a concept that should be consigned to the past. Instead of death and suffering, the New Big Five is about life, creativity and celebrating the natural world – highlighting threats facing the world’s wildlife, including the illegal wildlife trade, habitat loss and climate change.

Elephant reaching for high branches, Ruaha National Park, Tanzania by Graeme Green (Credit: Graeme Green)

Photography plays an important role in shaping how people feel about the animals we share the planet with. “I strongly believe in the power of beautiful images to reach people’s hearts,” says Daisy Gilardini, whose work focuses on polar bears, penguins and other wildlife in the polar regions. “Science can provide data and suggest solutions. If you like, science is the ‘brain’, while photography is the ‘heart’. It’s only by having science with photography that we can move people to action.”

Polar bears, Wapusk National Park, Manitoba, Canada by Daisy Gilardini (Credit: Daisy Gilardini)

Many wildlife photographers, like Gilardini, Marina Cano, Marsel van Oosten or Thomas D Mangelsen, create images that often reveal animals’ ‘human’ qualities: family bonds, playfulness, humour or tender moments. “With gorillas sharing 98.4% of our genetic make-up, it’s more a case of photographing ‘someone’ than ‘something’,” is how Nelis Wolmarans describes his work with the great apes.

Mountain gorilla, Virrunga National Park, DRC by Nelis Wolmarans (Credit: Nelis Wolmarans)

While some argue against humanising animals, others see it as an effective way to get people to care. “One of my pet peeves is scientists saying ‘Don’t anthropomorphise animals’,” says National Geographic photographer Steve Winter. “And I say ‘Do.’ The closer we are to animals, the more we understand that they have personalities, feelings.”

Across time and cultures, lions have been depicted as noble warriors, kings and even gods. Aslan the Lion in CS Lewis’s books is essentially Jesus in big-cat form: holy, pure-spirited, undefeated by death. Lions are the gatekeepers of palaces and cities. Babylonian goddesses rode chariots pulled by lions. Today, lions are logos on cars and football jerseys.

Lion brothers, Naboisho Mara Conservancy, Kenya by Graeme Green (Credit: Graeme Green)

Perhaps because they’re an enduring symbol of strength and bravery, many people assume lions are doing fine. But over the last 25 years, we’ve lost half of Africa’s lion population – the decline largely caused by habitat loss, human-wildlife conflict and the bushmeat trade. One of my photos, Lion Brothers, shows a moment of affection between two adult male lions. Lions are powerful hunters, an apex predator, but I also like taking pictures that show interactions, grooming and cleaning, feeding or relaxed family time. Lions need to be seen as more than a symbol.

Photography can show people what’s at stake; what we’re at risk of losing. “I want people to see animals in the most glorious way,” says Clement Kiragu. “It’s my hope that by showing people the beauty of the natural world, it can maybe change people’s perception, and start convincing some people that ‘You know what? These creatures deserve to be saved. These are the creatures we share the planet with, and they deserve to be here as much as we do.'”

Wild by Clement Kiragu (Credit: Clement Kiragu)

But people also need to understand harsh realities, and photos help get urgent messages across. “The world’s moving at such a fast pace now that we need potent photography to stop us in our tracks,” says Jamie Joseph, founder of Saving The Wild, who work to dismantle rhino-poaching syndicates. “I’m a writer and a wildlife activist. If I really want to be heard online, I lead with an emotive image… Visual storytelling is the difference between being heard or being forgotten.”

A bleak picture

More than a million species of animals, insects and plants are at risk of extinction, many in the next few decades, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The urgency of the wildlife crisis is driving darker photographic work, like Brandt’s, as well as the reporting of Britta Jaschinski, co-founder of Photographers Against Wildlife Crime, whose disturbing black and white images show elephant’s feet ‘ornaments’ and tigers and orangutans performing in circuses, and conservation photographer Paul Hilton’s work on pressing issues, from the shark-fin trade to palm-oil destruction.

Stirton’s photos from the frontline include a butchered, dehorned rhino carcass in South Africa, which won the 2017 Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition, and a gorilla killed by paramilitaries in the Democratic Republic of Congo. “I’m very influenced by James Nachtwey, who I regard as the godfather of photojournalism,” Stirton explains. “He manages to take horrific scenes and photograph them in a compositionally masterful way. I’m always looking to make images that have both an aesthetic quality and a quality that’s going to move you.”

Stirton’s Pangolins in Crisis series brings a focus to lesser-known animals. “Smaller species have been disappearing at an incredible rate,” he says, “because we’re not paying much attention to them and because a lot of people haven’t actually heard of them.”

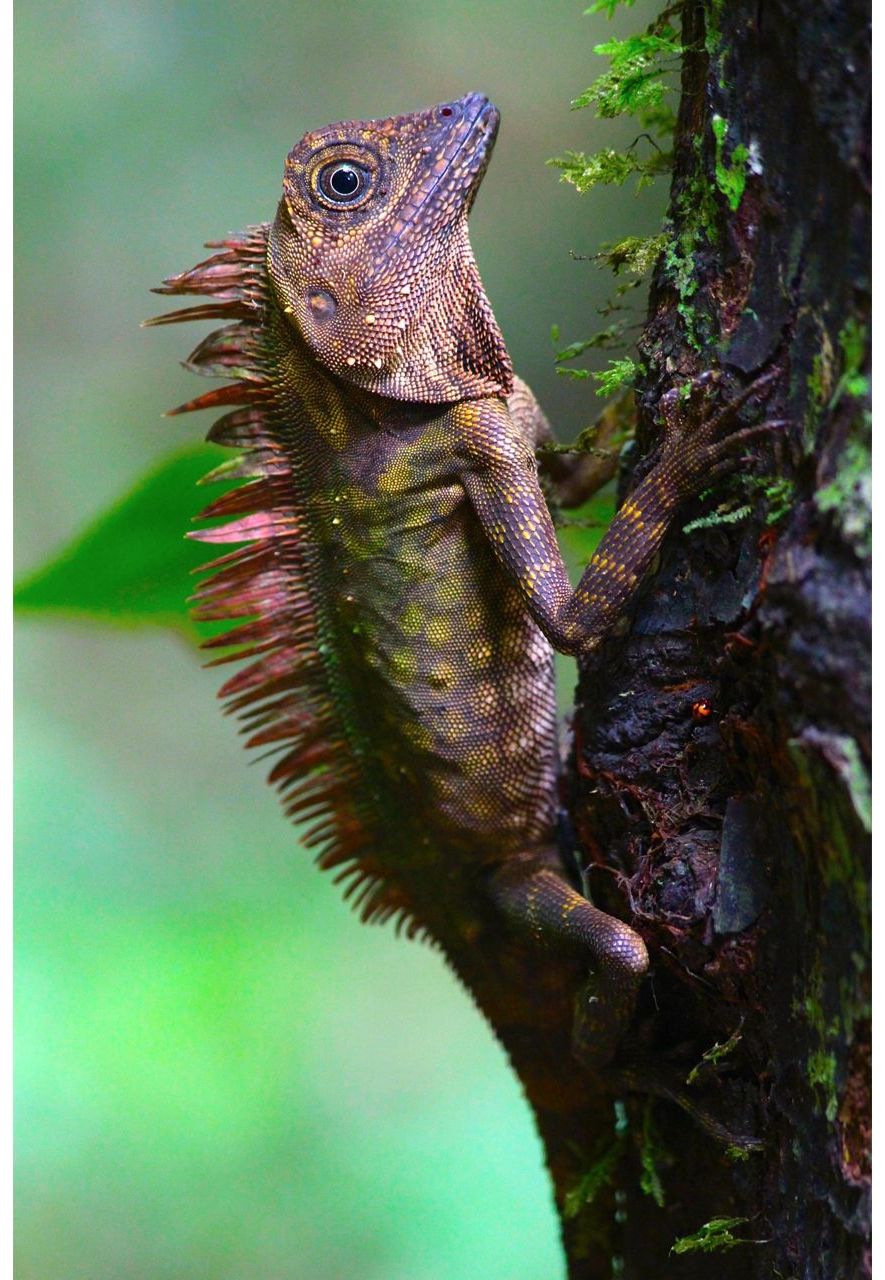

Blue-eyed lizard, Gunung Mulu National Park, Sarawak, Malaysia by Graeme Green (Credit: Graeme Green)

That’s starting to change, as conservation photographers work to broaden out the species seen as ‘worthy’ of attention. Often captured with camera traps, remote-control cameras and other technologies, unfamiliar species or pictures that open up ‘secret lives’ are being seen more. “As humans, we often have a bias towards feathers and fur,” says Christian Ziegler, a photographer with a background in tropical ecology. I also love to do stories about plants and invertebrates. I’m more interested in less well-known species, rare species that are endangered. I want to highlight the lives and habits of these species, how they interact with their environment, how they raise offspring… We’re driving our fellow species to extinction. This is why I take photos: to create stories that hopefully have impact.” Many species that are ignored, little-known or unheard of are fascinating to watch. I’m also as interested in photographing small, less famous creatures as I am lions and gorillas, too, from frogs and lizards to rollers and bee-eaters. Photographing those animals that don’t often make it into calendars or onto posters can offer a reminder that every single species, from iconic ambassadors to ‘unsung heroes’, is too valuable to lose.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.