Delftware porcelain – the global story of a Dutch icon

The sweeping history of Delft’s exquisite blue-and-white ceramics stretches across the globe. Cath Pound explores an intriguing tale of obsession, piracy and long-held secrets.

T

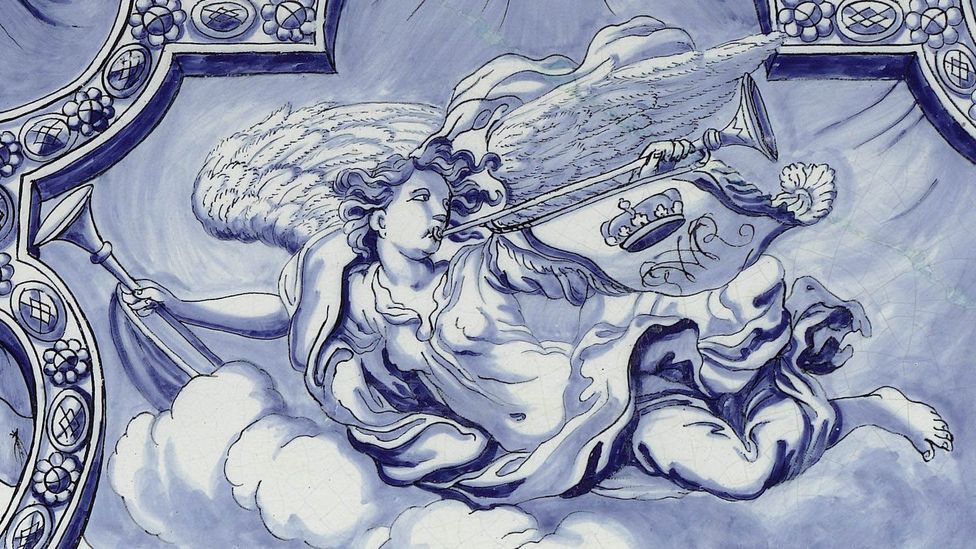

The striking blue-and-white ceramics from Delft, which this year celebrate their 400th anniversary, have come to epitomise the Netherlands. Yet Delftware’s route to production and popularity relied on a truly international cast of characters. From Chinese porcelain makers, via Middle Eastern ceramicists to a British Queen and her French interior designer, this national icon has truly multi-national origins.

More like this:

– The floral fabric that was banned

– The quirky charm of Norwegian design

– What you didn’t know about colour

Chinese potters in Jingdezhen, a kiln city in the inland province of Jiangxi, first developed the technology to fire true porcelain in the 14th Century. Its production requires kiln temperatures of 1,300C, high enough to turn the glazing mixture to glassy transparency and fuse it with the clay body, after which designs are trapped between the two layers. The blue and white aesthetic the Dutch would later make their own was itself created to appeal to the Persian market who decorated their own ceramics with cobalt blue designs but could not match the whiteness of Chinese porcelain.

These exquisitely patterned, translucent creations first started to appear in the cabinets of curiosity belonging to Europe’s elite in the late 16th Century, brought overland by traders via the Silk Roads and Venice. “Nobody knew the secret of porcelain and that’s why it was so fascinating,” explains Suzanne Lambooy, curator of an exhibition highlighting the finest Delftware at the Kunstmuseum in the Hague.

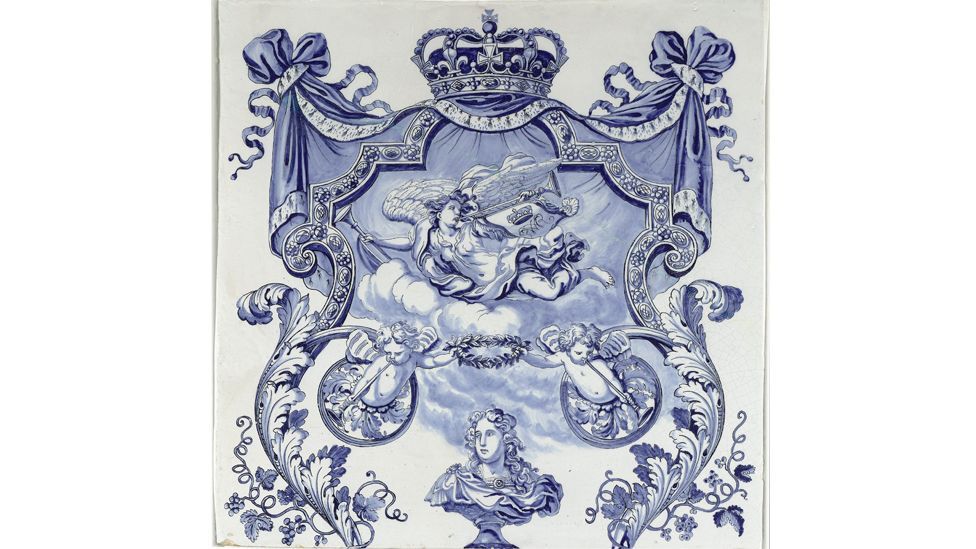

An elaborate 1690 Delft wall plaque is displayed in an exhibition at The Hague’s Kuntsmuseum (Credit: Rijksmuseum)

Most Dutch readers first learned of porcelain’s existence in 1596 from Jan Huyghen van Linschoten – a Dutchman who had travelled to India in Portuguese employ. He described pieces he had seen in the markets of Goa as “so exquisite that no crystalline glass can be compared to them”.

Not only did Van Linschoten whet the appetite of the coming generation of Dutch world traders, he also provided the means for them to begin to break the monopoly their great rival Portugal had hitherto enjoyed on maritime trade – by publishing secret charts and navigation guides that enabled them to reach the East Indies. However, the first major shipment that arrived in Holland was not the result of trade but piracy. In 1602 a Dutch fleet seized the Saint Iago ship, belonging to their Portuguese rivals, off St Helena. The contents were auctioned at Middleburgh in the South of Holland where buyers from all over Europe fought for a piece. The next shipment came the same way the following year, when the Santa Catarina was captured off Johor in the Strait of Malacca. The haul of 100,000 pieces was auctioned in Amsterdam, with buyers prepared to pay whatever they needed to acquire a piece. “They were fascinated by the shiny glaze, the white body and the unknown patterns and decorations which came from a new world,” says Lambooy. “It was something so spectacularly new that it became an instant fashion.”

A 2019 design for the Blue Room in the Palace Huis ten Bosch, featuring a 1690 Delft vase (Credit: Scheltens and Abbenes)

Of course the Dutch wanted more, but they knew that it was in their interests to secure legitimate trading links with the Chinese. The founding of The Dutch East India Company in 1602 was an indication of their desire to become the dominant maritime trading power, a desire that would see colonial expansion and abuse. But in the Chinese porcelain trade, at least, they found themselves very much the subservient partner.

Dutch traders were forbidden to travel inland to Jingdezhen so that the ceramicists could protect their secret. Instead they were required to order from intermediaries, and then Chinese ships would deliver them to Batavia (now Jakarta), the trading outpost the Dutch established in 1619, which would eventually become the capital of the Dutch East Indies. Dutch merchants were also obliged to pay homage to the Emperor in order to maintain their trading rights.

The popularity of Chinese porcelain meant that almost immediately ceramicists throughout Europe started to imitate it. The most successful of these imitators were, of course, those from Delft. But this was far from a uniquely Dutch triumph. “The tin-glazed technique used for it came from the Middle East to Islamic Spain through the island of Majorca, where the name majolica came from,” explains Lambooy. “In the 16th Century it then went to Faenza, where faience pottery comes from, and then to France.” A lot of Huguenots (French Protestants) then fled to Antwerp to escape persecution but following the fall of Antwerp to Spanish Catholic forces in 1585 these refugees were forced to flee further north. “Potters with Italian roots moved everywhere,” says Lambooy, “although it’s unknown why Delft exploded to become the centre”.

One theory is that beer breweries fell into disuse, allowing potters to take them over, and the fact that Delft was a major centre of the Dutch East India Company meant that there were plenty of Chinese originals for them to imitate. Whatever the case, after a period of experimentation the potters of Delft were producing pieces with all the characteristics of tin-glazed Delftware as we know it by 1620.

Lavish tastes

Early Delftware was a curious hybrid, with plates featuring a Dutch countryside scene in the centre but with the rim divided into panels, characteristic of Ming Dynasty porcelain. The Dutch would also occasionally misunderstand or misinterpret Chinese imagery. Peaches are a symbol of longevity in China but would appear resembling oranges on Delftware.

Intriguingly the tiles which are so frequently associated with Delftware were in fact made throughout Holland. “They were a broad national product,” explains Lambooy.

A 17th-Century bust of Queen Mary ll, who did much to popularise Delftware (Credit: Loan from Rijksmuseum)

Although Delftware was created as a cheaper alternative to Chinese porcelain, which remained in great demand throughout the 17th Century, the ceramics produced were still the finest in Europe. Elites from across the continent, including the Sun King himself, Louis XIV, would order pieces.

However, it would take a British Queen to turn Delftware into a truly luxurious product. Mary Stuart, the daughter of James II, had married the Dutch Prince William of Orange, in 1677. The couple became King and Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, when English aristocrats invited the couple to take the throne from James in order to avoid a Catholic succession.

In Holland, Mary had become enraptured with Chinese porcelain, and also bought Delftware pieces for the couple’s Het Loo Palace, although these were mostly smaller items such as flower vases and dishes. Once she was also Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland, her tastes became far more lavish. “It seems that Mary thought, ‘when I have the best potteries in Europe making the most beautiful Delftware so close to the Hague, why not decorate my palaces with Delftware and order what I like to be made for them?,'” says Lambooy.

The Delftware flower pyramids are a highlight of the exhibition (Credit: Gerrit Schreurs)

Her commissions resulted in the largest and most technically advanced Delftware ever produced, including the elaborate vases and flower pyramids that literally and figuratively mark the high point of Delftware production. Created from several different pieces, they “are very difficult to make in order for them to be stacked in an absolutely straight manner,” says Lambooy.

These pyramids, today thought of as so archetypally Dutch because of their association with the display of tulips, had long been thought to be influenced by the porcelain pagoda at Nanjing which had been described in awe-struck tones by Johan Nieuhof in an account of a Dutch East India Company visit to the Emperor of China in 1665. However, Lambooy has uncovered evidence that suggests Mary’s French interior designer, Daniel Marot, may also have played a part in their design. A pyramid-shaped grave monument he designed with nozzles for candlesticks on its ribs is strikingly similar. “Our new theory is that it is obviously a French influence on the design of the shape the Dutch potters create but the decoration and colour scheme is Chinese inspired,” says Lambooy.

Smaller Delftware items such as pots for exotic spices, including cloves, mace, cinnamon and pepper are an indication of the Dutch Republic’s colonial expansion, no doubt a source of pride for William and Mary. But the monopoly the Dutch East India Company had on the spice trade had a devastating impact on indigenous populations. A more explicit indication of the impact of colonialism can be found in a number of unusual Delft vases which are Chinese-influenced in every way – except for their depiction of black slaves. Although there is no evidence that enslaved people worked in the Delft potteries, whoever designed the vases was more than aware that slavery was part of Dutch culture, both at home and in the colonies.

Contemporary designers Scheltens & Abbenes were inspired by Delftware to create a wall covering for the Palace Huis ten Bosch (Credit: Scheltens and Abbenes)

Delftware fell out of favour in the 18th Century when ceramicists in Meissen discovered the secret of porcelain, and English creamware became the choice for everyday use. However it began to return to popularity in the late 19th Century when antique collecting saw Dutch 17th Century style very much in vogue. Intriguingly, this may have been the first time when it was seen as a typically Dutch product rather than a Chinese imitation.

That it continues to have such relevance today owes much to Queen Maxima, the Argentine-born Dutch queen consort of Willem-Alexander, king of the Netherlands since 2013. Maxima was instrumental in the creation of an elaborate new Delftware dinner service for use at state functions. “To me that’s where the fascination lies. Mary was an English Princess who gave the Dutch an iconic product, and now we have an Argentinian Queen who is promoting it again as a symbol of the Netherlands,” says Lambooy. It seems Delftware’s international journey is far from over.

Delftware Wonderware is currently at the Hague Kunstmuseum, Netherlands.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List, a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.