A Song of Ice and Fire is a popular series of fantasy books written by George RR Martin that have sold more than 90 million copies around the world. The first in the series, Game of Thrones, gave its name to the hugely successful TV programs that serialized the novels.

The work is often praised as a fine example of the art of storytelling. It has an epic scale, a complex narrative and a broad range of characters that interact with each other. Important characters are killed off, often at surprising and unpredictable moments. But while the story is complex, it is still possible for ordinary readers to follow.

And that raises an interesting puzzle. Given the sheer number of characters — over 2,000 of them — how do readers keep track of them all? And how does the author of this sprawling tale stop it becoming hopelessly complex and confusing?

Now we get an answer thanks to the work of Thomas Gessey-Jones at the University of Cambridge in the UK and a number of colleagues. This team has mapped out the social network from the entire series and measured its key properties.

They say the network is remarkably similar to the real-world ones that humans have evolved with. “We have shown that the network properties of the society described in Ice and Fire are close to what we expect in real social networks,” says Gessey-Jones and co.

Network Tricks

And they go on to say that studying this network reveals some of key the tricks that George RR Martin uses to keep readers engaged and the story manageable.

Complexity scientists have long known that social networks have certain specific properties. For example, the number of people humans can have meaningful interactions with is limited by our cognitive ability to remember their names and the details of our dealings. That limit, about 150, is known as Dunbar’s number after the behavioral biologist who first proposed it (and who is a co-author with Gessey-Jones).

Gessey-Jones and co say there are over 2,000 characters in A Song of Ice and Fire series. But the story is divided into chapters, each of which is seen from the point of view of a single character. These are obviously the most important characters and there are 14 of them in total.

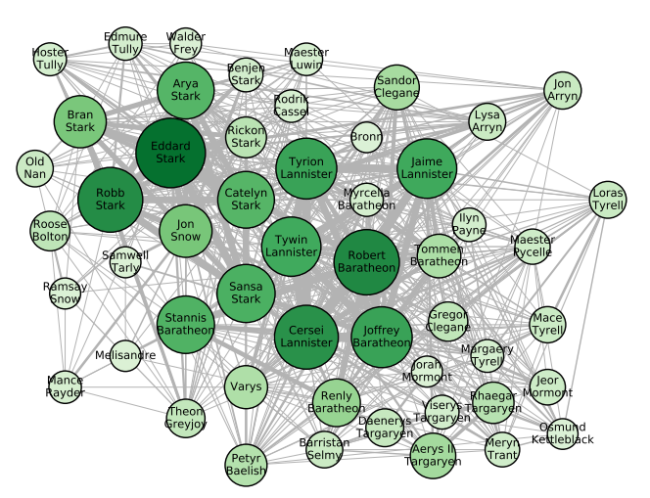

The researchers map out the social network by making each character a node in the network and linking nodes if the corresponding characters meet in the text or if it is clear from the text that they know each other. The team then study how this network changes throughout the novels as new characters emerge and others die off.

Network theory offers various ways to characterize networks, independently of what they represent. One is property is the “degree” of the network–the number of other characters each node is linked to. In this case, the average degree of the 14 main characters is 154. This is remarkably close to Dunbar’s number and one of the features that makes the story credible.

That shows why Martin’s technique of telling stories from the point of view of key characters is so effective. “By relating the story from the points of view of different characters, the total number of interactions at any given stage remains within the average reader’s cognitive limit, making it possible to keep track of these relationships,” say Gessy-Jones and co.

The degree of a node is also a measure of its importance in the network, so this provides a way to objectively measure the importance of the characters. When the researchers do this, nine of the top ten characters are also those with their own point-of-view chapters. And the top ranked character by degree is Jon Snow, arguably the most important character in the series.

The team also studied the distribution of deaths over time. One of the features of the books is the unexpected and seemingly random deaths of some of the most important characters.

To study the pattern of deaths, the team make an important distinction between the order of events in the fictional world, which they call story time, and the way the reader experiences them in the book, which they call discourse time.

It turns out that the time between the deaths, as experienced by the reader in discourse time, follows a simple geometric distribution. However, in story time the deaths follow a power law that is remarkably similar to the way human-related events are distributed in the real word. This is, say the authors, “another sense in which the fictitious world of Ice and Fire bears quantitative similarity to the real social world.”

That’s interesting work that provides insight into the way Martin creates a sense of realism in this fantasy world. Clearly, the fiction cannot become so complex that readers can no longer follow it.

“If the story is allowed to become too complex, there is a threat of the average reader becoming cognitively overwhelmed and the story becoming chaotic and unfathomable,” say the researchers. “Ice and Fire avoids this; although more than 2,000 characters appear, readers and TV audiences alike remain avidly engaged.”

Pattern of Deaths

And the key techniques are to tell the story from the point of view of just a small number of characters; and to ensure that the patterns of deaths follow the specific power law that occurs in the real world.

That is consistent with other research examining the nature of fiction and story-telling. For example, Dunbar and others have shown that readers enjoy stories most when the complexity matches their own the cognitive abilities. This is usually determined by the number of characters in each scene.

George RR Martin cleverly ensures that his readers are never overburdened in this way, say Gessey-Jones and co. “We show that despite its massive scale, Ice and Fire is very carefully structured so as not to exceed the natural cognitive capacities of a wide readership.”

Ref: Narrative structure of A Song of Ice and Fire creates a fictional world with realistic measures of social complexity: arxiv.org/abs/2012.01783